Combat Boots, Fencing Foils, and Art Auctions: Remixing "Raw Power" (Part III)

After a years-long, multi-continent search for missing tapes, the remix was ready to start. But...who would the new version piss off? And who really owns The Stooges' legacy, anyway?

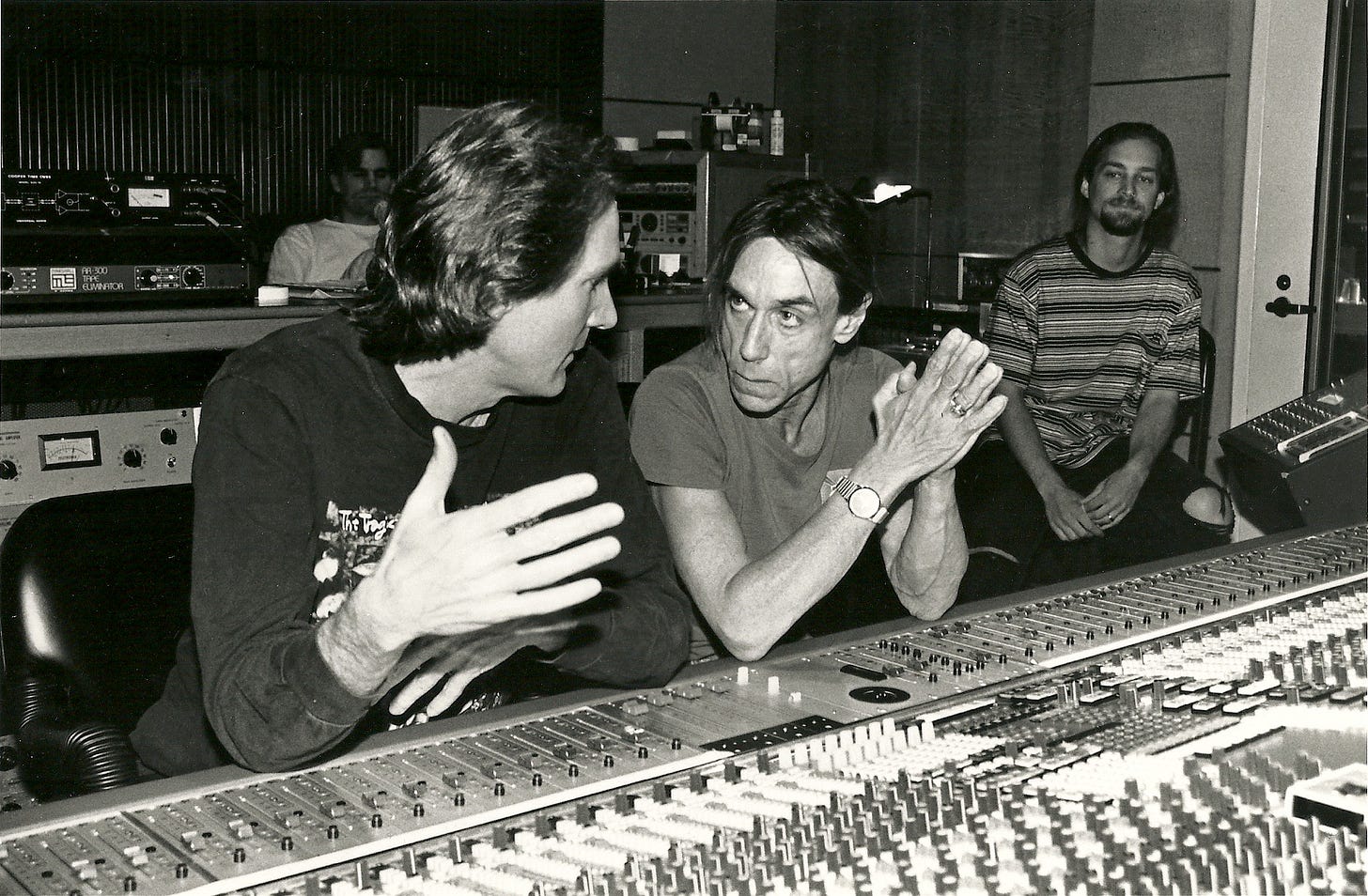

When we last visited the Raw Power remix saga, Iggy Pop and producer Bruce Dickinson had finally gotten hold of the original multitrack reels—though not the tape Steven Brown had stumbled upon in his Brussels attic. In October of 1996, Pop, Dickinson, and remix engineer Danny Kadar convened to start the project in earnest.

Technical Note: When magnetic recording tapes are old or have deteriorated, briefly baking them in a low-temperature oven can temporarily renew their emulsion (or “backing”) and prevent them from physically disintegrating.

Reverse Engineering a Lost Classic: At the Mixing Desk

Bruce Dickinson: I told Iggy: Let me know what your schedule is, and I'll get the reels and make sure they're in decent condition—or we can make them in decent condition, bake them. They were Scotch reels, fortunately. Not Ampex, or there'd be a lot of decay. Scotch reels, you can just take them out of the box—even if they're from the 1950s—and put them on the machine and they'll sound beautiful.

When Danny [Kadar] and I were working on the Cheap Trick reissues, we were standing there with our fingers manually adjusting the tension on the reels to keep the emulsion from coming off, so we could make copies of the two-inch masters. We knew we had one play, probably, and that was it.

Danny Kadar: The myth is that Bowie mixed it in two days. [Iggy] said the reality was that Bowie mixed it in one. [For the remix], me and Bruce would show up and pick a song to work on, get it to where it was good, then Iggy would come in at lunch time. We would order lunch, and we'd all eat together and listen to the mix. And Iggy would have very apropos suggestions about little things. You print the mixes, you move on to the next one, Iggy splits.

In the meantime, he was going to art auctions. Do you remember the 7-Up commercials with the guy with the big smile? (The actor’s name was Geoffrey Holder.) He had an amazing collection of Haitian naive art that was being auctioned at Christie's. Iggy loves that kind of very bright, rugged art. So he's like: “Yeah, I bought some stuff!” Things that were little bizarre. I think at that point his then-wife was like: No, you cannot hang that in the bedroom.

The mixing process you're talking about is like reverse engineering, sitting there with as good a pressing as you can get—if I had an analog tape, I would reference off of that. Listening to what's going on, and then kind of assessing what was done, not only EQ and compression wise but also like effects wise and panning wise and everything in the mix. You're trying to make it slightly more high fidelity—because the original mix was kind of rugged—but you also want to honor what was done because it's a classic record, so you don't want to get too far away from it. Once the balance is kind of close, when you do an A/B it's not shifting your sound stage so much.

Iggy was saying: “You know, this record was always a little too bright for me. A little too…you know, trashy.”

It's just a little difficult to listen to because of the way the low end wasn't wrapping around the top end. The top end is amazing, which is why people love that record. It's got this incredible aggression to the guitars. The stuff below it…there’s a little bit of sludgy bass, but you don't have that propelling feeling from the drum kit and the bass as a rhythm section. What we’re missing is a bunch of good low end to give your ear a cushion.

Seth: Being a bassist, I have to ask: Why does the bass on the original mix sound so…absent?

Danny: It wasn't recorded particularly well [but] it wasn't bad enough that you couldn't use it. It was a distorted amp sound, not incredibly punchy. I want to say it was an SVT or something like that.

[The recording engineer was probably] like: “Well, that's it, that's what you're playing!” I mean, are you going to get into a fight with the Ashetons? You're going to let those guys do whatever they want!

I did some reamping of the bass track; we put it through a flip top (Ampeg B-15) just to give it some of that roundness on the bottom.

We also rented a Roland Time Cube, which is basically a vacuum hose in a box with a speaker on one side and a microphone on the other, and gives you a kind of weird delay effect. Iggy said that had come out while they were making that record and it was on something that he liked, and so they used it on some things. I found it not to be very endearing. It's just like a crappy effect, but that's what they were using. So it's on there.

Then we did something you're not supposed to do in a reissue: make it a little bit better, a little bit more modern. I didn't add anything spatially, reverb wise or ambiance wise; that wasn't in the mix. Any experimental stuff I was doing—which was not much—was really applying kind of like a ‘90s rock mentality. Bruce would be like: “What would you do if this was a Nirvana record? Where's the through line?” But in reality, you can't change it all that much, because it is what that band played. It's just a really good band.

“Extraordinarily Dangerous Behavior”: The Stooges’ Studio Swordplay

Seth: Were there things on the tape you didn’t use?

Danny: I would try to put in every track that was on the multi, but some things didn't make it. Iggy told me they went out and bought combat boots because they wanted to record themselves stomping like an army. And sure enough, that's on there. It's not on the record because it doesn't sound like an army; it sounds like a bunch of dudes in a very expensive studio marching across the floor.

Bruce: For the song “Search and Destroy,” we're listening to all the stuff and there’s all this…what I'll call “sonic clutter.” And it's chaos. And I said: What is all that?

And [Iggy] goes: “We went out and we bought swords so we could have a sword fight and record that. You know, fencing foils and epees. You gotta remember the times…we were all, you know, feeling no pain. And we were running around the studio literally with swords, having duels and clashing and just making a racket with every sort of metallic implement…[pauses]. Yeah, that shouldn't be on there.”

Danny: You know, I'm a fencer, and I'm like: That sounds incredibly dangerous. Like, I don't let my kids play around with the epees unless they're wearing a mask. For most of the population, it would be dangerous. I might argue that for the Stooges in 1972 it would be extraordinarily dangerous.

Bruce: Iggy wanted to push [the volume] to the max, because he wanted that distortion. In the mastering process, we had to do a lot of work just to get it so it would work without coming up with an album that would skip.

What's amusing is after we're all done, we already had the idea of at some point doing a double album that had the new mixes on one album and the old mixes on another. And we also just wanted to remaster the original tape for posterity. So I went in with Mark Wilder and did that, and I sent the result without comment to Iggy. I talked to him the next day, and he said: “Bruce, what did you do?!?”

And I said: We didn't do anything but master properly! Now, in fairness to the people who mastered your album originally, there are a couple factors.

One, we have a lot better equipment than we did in 1973, but two: Imagine your album coming into a little mastering room to an engineer who had been working for Columbia Records since the ‘40s, who spends most of his time—even in 1973—mastering maybe the occasional Janis Joplin album, or Leonard Cohen. He's also doing a hell of a lot of Robert Goulet albums, or Andy Williams, because they’re still putting those out. What if you're that guy and you encounter Raw Power by Iggy and the Stooges? [You’re gonna be like]: “I don't know what the hell's going on!”

And [Iggy] goes: “Well, I still prefer the one that we just did.” And I laughed: Understood, they're both the same…but different. You know, some people will be upset and some people won’t. He goes: “I know. People like what they're used to.”

Seth: Are you happy with how the project came out?

Bruce: Oh, very, very. And I'm happy because it drew a lot of attention to the album in general. I like both versions. I know that sounds like I'm being wishy washy, but I really do. There are some songs—like the new version of “Gimme Danger”—that I think are staggering. It's almost like listening to a mono and a stereo of the same album, [like an] old Stones album.

The Missing Stooge: Ron Asheton’s Take

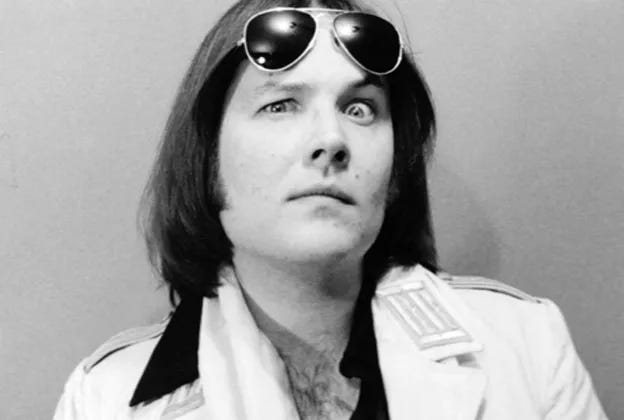

One person decidedly unhappy with the new mix was Ron Asheton, the former Stooge who—along with his brother Scott—quit the band in 1971. When Iggy and new guitarist James Williamson decamped to London the following year to record Raw Power, the Ashetons were grudgingly rehired, though Ron found himself demoted to playing bass.

According to Don Fleming—archivist, onetime Sonic Youth manager, and member of Washington, D.C.’s Velvet Monkeys, among many other duties—was an associate of both the Asheton brothers during this time. And he knew Ron he wouldn’t be pleased with the remix.

Don Fleming: [I told Ron] You know what? When Iggy's Raw Power mix comes out, I'll bet you're gonna go: “We always used to say how bad the original David Bowie mix of Raw Power was.” When you hear Iggy's mix, I guarantee you're gonna say: “Man, remember that great mix David Bowie did?”

Ron Asheton (interviewed by Ken Shimamoto, 1998):

"So I got the advance copy from [Iggy’s] manager, and I listened to it. Basically, all Iggy did was take all the smoothness and effects off James [Williamson]'s guitar so his leads sound really abrupt and stilty and almost clumsy, and he just put back every single grunt, groan, and word he ever said on the whole fuckin' soundtrack. He just totally restored everything that was cut out in the first mix, and I thought: ‘Damn, I really did like the old Bowie mix better’."

Asheton died in 2009; we learn more about his side of the story from Fleming.

Don: I had produced a record for Ron Asheton's project he had with Niagara, Dark Carnival. I crashed at Niagara’s house; it was very low budget. The bass player had the studio and it was just like: “Yeah, get in here and work with Ron.” So we did that, and that came out.

And then I was working with [music supervisor] Randall Poster and he was doing the Todd Haynes glam-rock film Velvet Goldmine. [Randall] came to me and he was like: “We need a Stooges. Do you want to put together a band to do it?” And I was like: “How about Ron Asheton?” And I got Thurston [Moore], Mike Watt, Steve Shelley, and Sean Lennon did part of the sessions. Then we had Mark Arm, who sang the songs that were meant for the movie, and we also ended up with Dave Pirner singing something. Ron sang two songs that were amazing—just to hear him singing! And so we had this great time and ended up making a whole record and giving them one song for this movie.

Jay Mascis was showing up at the studio kind of trying to horn in, wanting to play. And we were just like: “We’ve got, like, four guitar players already!” So then he started his band with Ron and Scott, and they started just doing Stooges stuff. And so all of this caught Iggy's attention and he came calling and said: “Well, if all these clowns can put together Stooges lineups, why can't I just do it with Ron and Scott myself?”

Seth: Was it complicated for Ron to revisit Raw Power?

Don: Ron did not like that record. I mean, he wasn't gonna like it no matter what, because he had to play bass on it. Well, I was gonna say he didn't like the original, or just didn't like the whole politics of it. I mean, they never played any of those songs [from Raw Power] when they did the reunion—until Ron was gone. He was not gonna play those songs. Even if he got to play guitar, he wouldn't do it. And the same thing happened in the studio where [the Velvet Goldmine supervisors] wanted one song from the third album, and he wouldn't play on it.

Seth: It's funny you bring that up. In a recent interview with Rick Rubin (on the Broken Record podcast), Iggy references Ron’s brilliance as a bass player.

Don: I said to him more than once: “Your bass playing is just phenomenal on that record. It's what what makes the record for me.” Just listen to his playing. He's not Dave Alexander; he's not Mike Watt. He's like Joe Bouchard from Blue Oyster Cult, those first three or four albums. If you listen to those bass parts, there's a lot going on there.

Seth: In that same conversation with Rubin, the way Iggy frames the creative dynamic is that he basically saw the natural genius of the Asheton brothers, and then sort of fed them their lines.

Don: You know, he's the front man and he's also in control of the narrative, right? He can say whatever the fuck he wants to, and he's mostly right. But I think the root of their sound was Ron and Scott. When you have two guys in the same family who play together, something sort of magical happens. I would not disagree with anything [Iggy] says, but Ron deserves all the accolades for making the music of the Stooges what it was. And that's the sound of punk for me.

I mean, again: I love Blue Oyster Cult. I love Black Sabbath, all that great heavy music, Atomic Rooster. But there was something about The Stooges for me. As a guitar player, I felt like Jimi Hendrix was it, he was the best. And then after that, it was Ron. I couldn't play like Hendrix, but I could try to play like Ron, and that was the learning experience for me as a guitar player. Listening to those records, I was able to sort of get my head around it.

Seth: The Raw Power remix aside, what do you think the impact of The Stooges reunion was for Ron?

Don: To watch him get back with Iggy, and…just that whole thing was amazing. I think the whole time they were very happy to be doing that. I think Iggy, too. I think they just knew it was a good fit. During that whole time, I don't know if Iggy did any kind of solo stuff. I think Iggy knew how good it was [just] to do that. [Pauses]…I was very lucky to have Ron in my life at all. A huge deal; He was such an influence.

Danny: I mean…it’s amazing how completely with it Iggy Pop is. Iggy is not foggy, he's just with it and knows what the important part of the songs and the albums are. It was one of those projects where afterwards you're like:

Fantastic — Stooges forever!