Dawn: Gaza, Jewishness, and the Price of Unmet Grief

For generations, my family denied our Jewishness. Now that I’m trying to come to terms with it, the question is: How? Sometimes, the answer is staring you right in the face.

I don’t believe in coincidence anymore.

When I fell into what I call “Medicine World”—the multiverse of ayahuasca ceremonies, MDMA-dispensing therapists, and various related subcultures—the notion of “coincidence” vanished forever.

It wasn’t that I stopped experiencing odd synchronicities—like imagining a long-lost friend’s face a few seconds before they phoned me out of the blue. I just stopped being surprised by it. Some new way of seeing had come online, an enhanced pattern recognition that may explain why animals such as reindeer and bear intentionally consume psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

Or hey: Maybe they just want to crush it at their tech jobs.

All this to say: A few days ago I found myself wandering through downtown Berkeley. I was pondering the war in Gaza, and all the ways it made me want to hide under a rock and simply forget I’m Jewish. At that very moment, I looked down at the sidewalk and saw a book staring back at me: Dawn, by Elie Wiesel. I bent down, picked it up, and read the front-cover blurb:

The anguish and loss of the moral Jew who has placed himself on the other side of the gun.

I had to laugh. Right on time. I took it back to my apartment and began to read.

Dawn isn’t about denying one’s Jewishness—the sort of compulsive code-switching that is in part my family inheritance.

But one of the book’s subtexts is the refusal to touch on grief—to replace it with vengeance, movement, and decisive action. And it cuts to the very heart of why for some people at least, the kind of self-denial I’ve unconsciously embraced can feel like the only safe option.

The book is set in 1947 in the British Mandate—the territory that once comprised present-day Israel, the West Bank, Jordan, and Gaza. The protagonist is a young man named Elisha, a terrorist—his word, not ours—fighting for Israeli independence. In his flat and unironic telling, “the whole of Palestine is one great prison.” But Israel’s turn as prison warden is still decades in the future. At this moment they’re the inmates, and the British troops patrolling the Mandate are the jailors.

Like Wiesel himself, Elisha has survived both Auschwitz and Buchenwald; like him, his parents, siblings, and friends have not. Having washed up in France, cauterized and bereft, he’s an easy mark for recruitment. When a mysterious stranger named Gad appears, seeming to know all his secrets, Elisha agrees, with hardly a backwards glance, to join the Irgun—the Zionist paramilitary group known in the book simply as “the Movement.”

Gad’s stories were utterly fascinating. I saw in him a prince of Jewish history, a legendary messenger sent by fate to awaken my imagination, to tell the people whose past was now their religion…from now on you will no longer be humiliated, persecuted, or even pitied. You will not be strangers encamped in an age and a place that are not yours.

On its face, Dawn isn’t about the larger questions—the righteousness of the struggle to found a Jewish state, the complexities of just how they should reinsert themselves into an overwhelmingly Arab territory. It’s a book that focuses keenly on a single night—and what will happen when dawn comes. One of the Movement’s foot soldiers, captured by the British, is to be executed at dawn. In response, the militants have kidnapped an English officer. In the inexorable logic of the struggle, if one man dies, so must the other.

Dawn is a fast book—I probably finished it in under two hours. And it’s driven by an awful, ever-ticking mainspring. From the first page to the last, we know precisely what is going to happen: Elisha—all of 18 years old—is going to kill the English hostage.

I’ve been to Israel just once, in 2006.

I was struck, as many visitors are, by the glaring juxtapositions, the way the ancient and the sacred jam up against the new and the profane. “A third-world country with first-world advertising,” said a friend, and that’s as apt a description as I can muster. Still, as I walked Tel Aviv’s sinuous wooden boardwalk at sundown, surrounded by throngs of sculpted, dark-haired young people, I felt something stirring inside me: the notion that as a Jew, I might actually belong here.

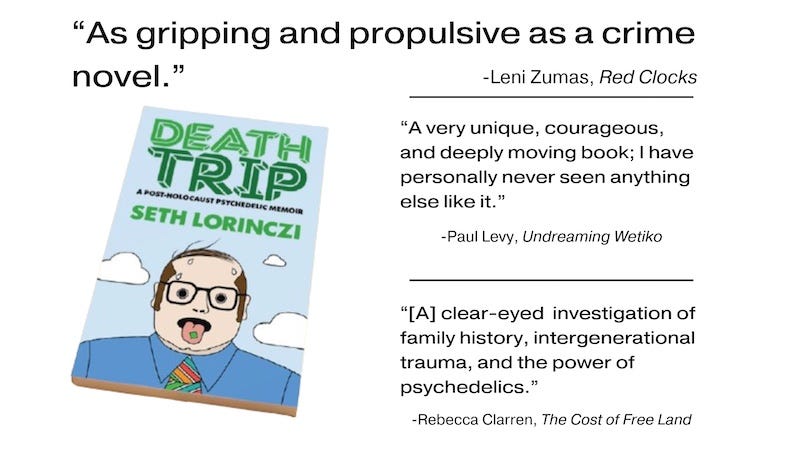

This was an unfamiliar sensation. For one thing, I’ve never much felt I belonged anywhere—certainly not any nation. Then there’s the Jewish Question. By my calculations, I’m at least the fourth generation of my family to more or less deny my own Jewishness. As I researched my just-published book—Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir—I grasped for the first time the lengths my ancestors had gone to in order to conceal or outright shed their identities.

Some of the ways were trifling: The way my father would bristle at stereotypically “Jewish” humor, or grow visibly uncomfortable when I asked about his past. Others were less so: How my grandparents and great-grandparents moved away from Jewish neighborhoods, or suddenly started attending Mass. Or changed their last name. Over and over and over, they’d felt the need to deny who they so plainly were.

There were other, darker aspects of my visit to Israel. Mixed in with the stunning sense of history not being cloaked in centuries of dust but active, vital and alive, intimations of violence were everywhere. Soldiers on leave (and everyone in Israel is a soldier) carried military-grade weapons in shopping malls and ice-cream parlors. Some were teenagers, barely older than my daughter is today.

One afternoon, as we drove past the city of Haifa, traffic suddenly came to a dead halt. Ahead of us was a police blockade and beyond that, just visible by the side of the road, a backpack. A team of demolitions experts in protective gear fussed around the bag. A few minutes later came the muffled THUD of an explosion. We drove past the backpack—it had been a child’s, the cartoon characters now shredded—and continued on our way.

As he paces the floor of an anonymous safe house, Elisha struggles through the longest night of his life.

Downstairs, locked in a basement cell, is the hostage: A British captain named John Dawson. But if he’s a prisoner, so too is Elisha, in his way. Though only recently initiated into the Movement, he’s been hand-picked by its leader—“The Old Man”—for this particular blooding.

I remembered how the grizzled master had explained the sixth commandment to me. Why has a man no right to commit murder? Because in so doing he takes upon himself the function of God. And this must not be done too easily. Well, I said to myself, if in order to change the course of our history we have to become God, we shall become Him. How easy that is we shall see. No, it was not easy…I found myself utterly hateful. Seeing myself with the eyes of the past I imagined that I was in the dark gray uniform of an SS officer.

As the hours tick inexorably towards daybreak, Elisha has a vision of sorts. The room fills with a throng of hungry ghosts. They’re all the people he’s lost: His parents and siblings, friends and rabbis and teachers and beggars, each demanding a rationale for the awful act he must perform. Poor boy, poor boy, they murmur.

As dawn approaches, the militants argue over whether Dawson should be granted a last meal. Elisha, barely stilling his anxiety, will do anything not to walk down the cellar stairs and look the man he’s to kill in the face. Instead, Gideon, one of his comrades, takes Dawson a paltry offering: A mug of coffee and a sandwich. Now, the clock ticking ever onwards, Gad—Elisha’s recruiter—beckons him close:

“Soon it will be day,” he observed.

“I know.”

“You know what you have to do?”

“Yes, I know.”

He took a revolver out of his pocket and handed it to me. I hesitated.

“Take it,” said Gad.

The revolver was black and nearly new. I was afraid to even touch it, for in it lay all the whole difference between what I was and what I was going to be.

The scene in which Elisha finally goes downstairs to confront Dawson is as finely drawn, tender, and excruciating as could be imagined. At Dawson’s invitation, Elisha sits down on the bed with him. He studies the Englishman, hoping in vain to find a way to hate him. He observes the officer’s hands—“smooth-skinned, with long, slender, aristocratic fingers”—and slips into a meditation on what such hands are capable of.

Back in the camps, Elisha had met a man named Stefan, a sculptor and an anti-fascist. When he was arrested by the Gestapo, the Berlin chief—“a mild, timid man” with astonishingly beautiful, even angelic hands—had donned a surgeon’s white jacket and cut off the fingers of the sculptor’s right hand, one finger per day, for five days. “Don’t worry,” the chief assured him. “From a medical point of view, everything is in good order. There’s no danger of infection.”

Still, Elisha can’t bring himself to hate Dawson.

“You hate me, Elisha, don’t you?” John Dawson asked, with a look of overflowing tenderness in his eyes.

“I’m trying to hate you,” I answered.

“Why must you try to hate me, Elisha?” He spoke in a warm, slightly sad voice, remarkable for the absence of curiosity.

Why? I wondered. What a question! Without hate, everything that my comrades and I were doing would be done in vain. Without hate, we could not hope to obtain victory. Why do I hate you, John Dawson? Because my people have never known how to hate. Their tragedy, throughout the centuries, stems from their inability to hate those who have humiliated, and from time to time exterminated them. Now, our only chance lies in hating you, and learning the necessity of the art of hate. Otherwise, John Dawson, our future will only be an extension of the past, and the Messiah will wait indefinitely for his deliverance.

My visit to Israel lasted nearly a month, an eye-opening and perplexing trip that, when it was all over, left me wondering how much I really knew.

I felt as if I’d been looking through a pinhole camera, seeing only the culture’s most obvious details while missing the finer ones visible only to those who’d grown up within it.

And yet this vantage point, limited as it is, affords a certain perspective. I experienced Israelis’ essential hardness, their quickness to rise to disproportionate anger. And I noted how many seemed to be suffering from some variation of PTSD: hyper-vigilant, furious, emotionless or absent.

It’s not hard to imagine why. One morning as I walked with a relative of mine past Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff Square, he mentioned the 1994 bus bombing there—one of two he’s witnessed. He described the weight of the silence following the blast, as if for a moment the experience of sound itself had been eradicated. That and the smell—horrific and indelible—of scorched flesh wafting through the warm air.

Can you imagine the lengths you’d go to protect yourself from ever experiencing such a horror again? I can. Easily. And yet every time I see a headline detailing another IDF raid gone awry—or perhaps having gone exactly to plan—all I see is another generation of bus bombers.

As I finished Elie Wiesel’s Dawn, I couldn’t help but think of the contradictions that lie at Israel’s very core. The country occupies a position of supreme military dominance over its neighbors, and many Israelis appear to be affluent and urbane. And yet few of them seem to be enjoying their supposed rewards. Nor do they seem interested in digging into the past, to tapping into and freeing the wellspring of unmetabolized grief. How can you when the situation demands vengeance, movement, and decisive action? And yet grief, when unattended, hardens into grievance.

One of Dawn’s motifs is the idea of night as a living presence, an unknowable being. At the book’s close, Elisha—deafened and dumbstruck by the act he’s just committed—walks upstairs to watch the sunrise. Gazing out the window at the last tattered fragments of darkness, he’s gripped by fear. In the final moments before the dawn he sees that darkness has a face, and that it is his own.

unmetabolized grief is a perfect way to describe it. it's inherited trauma. what would have happened/could happen if we learn to metabolize the grief?

Seth, I deeply appreciate witnessing your transformation, vulnerability and thoughtful questions you pose. I have also been grappling over the last year with my Jewish identity. I wrote about it earlier this year on this platform.

And I suspect we are in the same generation although I visited Israel in 1985 at the age of 15.

I also wondered where the assumption or maybe fact that Jews were not in the region during the British Mandate came from. Perhaps it’s my ultra sensitive nature now that hones jn on this and I mean no disrespect for your journey. Jews have been there all along and in all the neighboring countries for centuries but through persecution they have been cast out just like Christians have been.

I do believe that the collective grief and trauma for all the peoples in the region perpetuates this cycle again and again. How do we all heal together to witness this trauma so we can realize we are all connected and we all belong? A life long question that continues to break my heart.