Exit Naomi: Saga of a Punk Photographer

After landing at LA’s most notorious punk label, Naomi Petersen became one of the scene's hottest photographers, shooting Sonic Youth, Gn’R, Nirvana and everyone between. How did it all go so wrong?

For a split second we locked eyes.

She wasn’t from here, that much was clear: Baggy sweats, Vans, gnarly metal band t-shirts. Not like the D.C. punk girls in their frocks and DMs. We were standing outside, next to a darkened downtown building. It was April of ‘89. Back then, you noticed when someone new arrived. The scene felt small; Dave Grohl hadn’t joined Nirvana yet; Fugazi hadn’t released “Repeater.” It was intimate; it was ours. But in the weeks and months to come it seemed like she was everywhere: In the fetid, rat-infested basement of the old 9:30 Club; prowling the grotty performance room at d.c. space—different smell; different rats. She was beautiful and she knew it. With her spiky hair and kohl-rimmed eyes, she looked like she’d stepped right off the pages of “Love and Rockets.” She oozed cred.

It’s just a fragment of memory, so gauzy I can’t even be sure it’s real. But now that I know how her story ended, I can’t let it go.

In the late ‘80s Naomi Petersen was the underground photographer, documenting the scene—in her words—“at the speed of sound.”

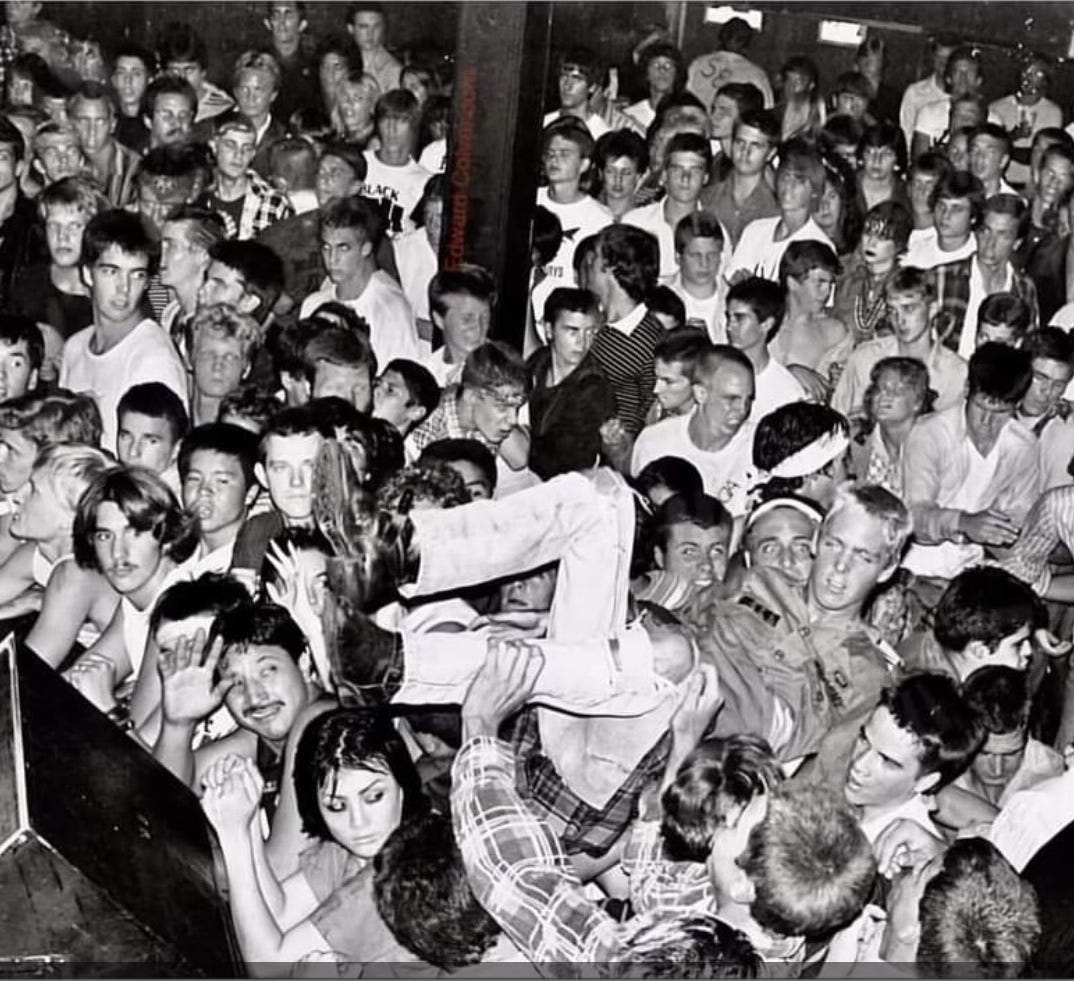

She shot with the eye of a fan; her photos, often uncredited in those hectic early days, captured nearly every band and scene that mattered: Black Flag, Minor Threat, Hüsker Dü and Sonic Youth—even the first known photos of Guns n’ Roses, just because she happened to work at the same restaurant as Duff McKagan. The images are unmistakably punk—harsh light, grainy focus—but they’re musical. They sing.

For a moment Naomi stood on the edge of the world; then it all went wrong. Whether it was the shift from punk to alternative or the sneaking suspicion there was no place she truly belonged, Naomi put down her camera. Few people knew how much she drank, and she hid it well until she couldn’t. She died of kidney failure in 2003, aged just 38.

What’s strange now is how little those who knew her are willing to share. Some don’t say anything; others admit to knowing her but don’t divulge the intimate nature of their relationships. It’s as if something is too painful, or too elusive, to commit to words.

But if in life Naomi was a drop of mercury unwilling to take solid form, in death she became something else: A catalyst. Her former boss Joe Carducci wrote a book about her (2007’s Enter Naomi: SST, L.A., and All That). Her husband and his new wife found something approaching redemption. And for the brother she left behind, Naomi’s death inspired a total rewriting of his life’s path.

Naomi was a change-maker; she made things happen. The tragedy is that she couldn’t seem to make them happen for herself.

These days Chris Petersen doesn’t seem like much of a hater, but he sure hated punk.

“I thought it was awful,” he told me. “I liked KISS and Led Zeppelin!” But he and his kid sister had always bonded over music—The Beatles, Cheap Trick—and the antic absurdity of Monty Python. And being the dutiful older brother, one night in 1980 he gave into Naomi’s pestering and took her to the show that changed everything:

“I took Naomi to see The Clash when she was 15. She talked me into it; it was at the Civic Center in Santa Monica in 1980. That night she became a punk rocker. After that she was picked on at school; people threw rocks at her. Being half-Japanese didn’t help.”

Just before she started high school, Naomi’s family moved from progressive Chatsworth to ultra-conservative Simi Valley. In Chatsworth Naomi was a popular kid, the class vice president. In Simi she was a triple-diagnosis outcast: Attractive, exotic-looking—at least by local standards—and a punk. Chris watched her back, but when he shipped off to UCLA she was on her own.

Naomi found her tribe in L.A.’s fierce and feral punk scene. Soon she’d brushed up against the demented universe of SST, the record label founded by Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn. After hooking up with the Flag’s infamous roadie / provocateur Mugger, a crisis forced her back again. One night in the summer of 1982, Naomi returned home late to find that her Mormon-raised father had locked her out. She phoned the office in a panic:

“Lights were out and I heard Chuck (Dukowski) answer quietly, wait, and then tell someone to come over. Naomi shortly came into SST weeping, and bleeding from her wrists. As Chuck led her to the bathroom sink I heard her tell him that her father had called her a tramp and refused to let her into the house. She must have driven back down through L.A., uncertain where to go. When she stopped driving she cut herself, got scared and called, throwing herself again on Black Flag’s mercy. Perhaps that seems a counterintuitive move, but I think it was smart of her.” -Carducci, Enter Naomi

Was it? In Henry Rollins’ words: “If you were a girl around Black Flag, you were going to get fucked. Not raped, but fucked.” In retrospect, a narrow distinction. But beautiful and music(ian)-obsessed as she was, Naomi had something SST needed: A Nikon F Photomic and the skills to use it. Soon she was put to work shooting the bands no one else would: Minutemen, Meat Puppets, Saint Vitus, Saccharine Trust and countless others. As her skills developed, she found that the audience for her work reached far beyond the self-sustaining universe of L.A. punk. And so she pulled up stakes and moved to D.C.

Naomi must have sensed the D.C. scene was about to blow up.

In early ’89, Fugazi had already been playing out for a year and a half. The music was taut, the shows awe-inspiringly intense; nothing stood in their way. Lungfish were as hair-raising as I imagine the Thirteenth Floor Elevators had been just twenty years before. And the Holy Rollers? Well, it’s a shame they never put out a record as good as they really were—especially in the early days when original drummer Max Micozzi was one of the most inventive percussionists ever to emerge from the scene.

Jim Saah—today a respected photojournalist and the author of In My Eyes, a collection of his photos from the punk era—remembers Naomi’s arrival:

“I started seeing her a lot; there were a lot of times where she was photographing from the other side of the stage. It’s a good trait for a photographer, to disappear and be a fly on the wall. [But] I never really knew what to make of her; I was young and intimidated by women.”

With her connections and her talent, Naomi quickly embedded in the scene. But then something went awry. She couldn’t decide whether to live in D.C., Zurich, or Berlin. Everyone wanted her—the Village Voice tried to recruit her—but she lacked the confidence to market herself. Instead she fell back on accounting and front-of-house food service work. Filmmaker Scott Crawford was a friend and co-worker in the early ‘90s, assigning her photo shoots for various music publications. At first, it wasn’t clear anything was wrong:

“I was such a fan of hers, and she had such a personality. She was really funny. She did accounting for (reggae label) RAS. She told me once that she once saw her position there advertised in the City Paper—she hadn’t come in to work for a while so they just assumed she’d quit. I wouldn’t hear from her for weeks, and then months, and then she’d pop back up. I was 19 or 20 and putting all these things together. [But] it was hard to be mad at her.”

After managing a disastrous tour for Saint Vitus, Naomi faded. No longer captivated by the music, she stopped going out to shows. She shot a wedding or two, but it clearly wasn’t her thing. When a beefy plumber named John Harper came to unclog her sink, he commented on the framed photo on her wall—Pantera, his favorite band. Desperate for something to cling to Naomi bet the farm on him; soon they were married. Bizarrely, Scott Crawford also had a connection with Harper:

“One day I called a plumber to fix something. The whole time I was thinking ‘Who is this guy? I know him!’ It turned out I went to high school with him, and he was just a total jock; I was so dismissive of him. But then—I don’t know how—[Naomi’s] name popped up. I couldn’t believe it. All I kept thinking was: ‘How do you go from hanging out at SST to this?’ In a way, it sums up her life trajectory.”

The rest is objectively awful. The familiar spiral of lies, hospitalizations, and rehab. Naomi’s brother Chris flew out to D.C. to pack up Naomi’s belongings so she could recuperate back at their parents’ house. It didn’t go well. She bounced a few more times between coasts, but her periodic attempts at sobriety never stuck. A doctor told her she’d die if she drank again, but she couldn’t seem to care. “I’m not going to make it, Chris,” she told her brother one night. She tried one last attempt at reconciliation with John but he wouldn’t take her calls. That night, Chris booked his sister a hotel room so she’d have someplace to stay. The next morning, a housekeeper found her body.

We live in a post-punk world.

Given the impact of the scenes she documented, Naomi probably would have been rediscovered sooner or later. What’s more surprising is the effect she had on the people she left behind. Like many of Naomi’s friends, Joe Carducci learned of her death years after the fact. Though he’s not the kind to display raw emotion, it’s clear her passing affected him deeply:

“I loved having Naomi and the girls around; they were fun and interesting. It was a surprise to learn she was dead—I learned it randomly. I want to make testimony to that period. She deserves better; they all did. I wanted to tell the story of people that didn’t get their stories told. And I’m a writer; I assumed there was an interesting mystery to solve.”

But in the months following his sister’s death, Chris was the only one equipped to go through the thousands of photos and negatives she’d left behind—never mind the countless others lost in an abortive move to Zurich or thrown out after she was evicted from her D.C. apartment. As he told me:

“When she died, it took me a while to go through her journals. Her writing got me; I’d dig into these boxes and learn about her. I had to commit to 8 to 10 hours a day scanning and cross-referencing dates and flyers and discographies and concert archives and matching them up.”

As Chris dug deeper into the grit of his sister’s life, something changed. He began going to punk shows and connecting with people who’d known her. Times had changed too, and as recognition that punk had been an important art movement grew, Naomi’s photos were seen as a critical body of work. Chris found a calling; today he helps stage exhibitions all over the world. Next year will see the first monograph devoted to her photography. As he put it:

“I’m living like she would right now. Talking to people, being in the front row [at shows]. I’m the only one who can really do it—the work of it.”

Still, there was one thing I couldn’t quite grasp. Chris loved his sister, but he’d gone far and above merely archiving her work. He’d reshaped his entire life, more or less remaking himself in her image. Why? I’d spoken with him a couple of times by now, and I thought I had a pretty good sense of who he was. After mulling it over a few days, I called him and asked him point-blank. He sighed. Then he said:

“I was leading a corporate life, but it never fulfilled what I thought I could do to make a mark in the world. [And] I feel bad. I left her behind and didn’t really connect with her after that. Are you okay? Are you getting bullied at school? She didn’t develop long-lasting relationships with girls. When I finally read the journals and understood, I felt like I had to carry on for her.”

We said our goodbyes and hung up. I sat quietly for a long moment, wondering what it might feel like to care for someone who cared so little for herself—or what my own friends might have felt as they watched me in my lowest moments. Then I texted Chris to thank him. He wrote back immediately.

“You’re welcome,” he wrote. “It helps me to tell the story too.”

Joe Carducci and Chris Petersen are in my circle, more or less; I expected they’d have something to say about Naomi’s death.

But what about John Harper, her former husband? As I pored through websites searching for clues about the final chapter of Naomi’s life, I stumbled upon a years-old social media post. It was written by Harper’s current wife:

“I come to [Carducci’s Enter Naomi] from a different place than every other reader. Naomi is my husband's first wife. For the past 15 years, she has been the beautiful ghost in my life, the woman I never met, but who I felt I had to measure up to. This book has taught me more about what made her into the person my husband adored, tried to help as he was working on his own sobriety, but ultimately had to leave to save his own life. I wish someone had made the effort to talk to him about his time with her. It took years for him to recover, to be open to loving another person in that way. But I know he loved her and it hurt to lose her.”

I was struck by how deeply Naomi had touched people, even those she’d never met. And I wondered why—after finding photography, the one thing that seemed to give her purpose—she’d so easily let it slip away. Those who knew her always feared she was a true nihilist at heart. Maybe, in death, she’d finally found a way to matter.

Which brings me back to that single memory—or not-memory—of Naomi.

All these years I wondered if I’d just imagined it. But in a journal entry reprinted in Enter Naomi, she references a show she attended just after moving to D.C.: Holy Rollers at d.c. space, April 15, 1989. I was there too. Now I remember standing outside space’s steel-and-glass front door. Naomi’s there, her face orangey in the glow of the sodium vapor streetlight. She’s wearing a trench coat against the early-spring chill. Do we exchange a word or two? Probably not. I’m 18 and painfully insecure. Then again, I suppose she is, too.

“I think only Naomi could float over any and all of the burnt bridges formerly connecting us…. Like us she was acclimated to the hopelessness and would charge fanzines as little as $5 to run her shots. But unlike us she was essentially alone. She fronted so well that even her best friends never knew she was in trouble—never knew she drank. She didn’t walk point for the Riot Grrls, or women generally. She often had a girlfriend with whom to sally forth, but those friendships didn’t last, and I don’t think she ever set up house with a guy until she retired into her marriage. Her mission was a solo long-range recon patrol behind enemy lines, or maybe ‘friendly’ lines. Just about the worst mission one could pull.” -Carducci, Enter Naomi

The punk scene was a home for the misfits, the ones who couldn’t find any other way into the world. For a fleeting moment it held Naomi, until it couldn’t any longer. All that’s left now is the evidence—those thousands of indelible images. But in Carducci’s words: “I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t trade the photographs for the photographer.”

Here’s the thing: The abyss is always right there. Punk gave us a way to touch on it safely—or, I suppose, not so safely. I found a way to belong, eventually, but Naomi never did. Now that I know how her story ended my mind fills in the blanks, returning again and again to that moment outside the show. Is that what I saw in her eyes, her abyss? Maybe. But really, I’ll never know.

Great article. Talented people destroying themselves with drugs or alcohol is a long, sad story. It would be great if there was a coffee table book of her best photos in large format, with memoirs from people who knew her and from bands that were on the scene at the time.

We used to lie and tell our parents we were spending the night at one another’s house and we would sometimes spend it at the houses of the bands or stay up all night with the bands. We would get horrible, horribly drunk as well. I always found it sort of interesting that these older males never messed with us teens. We could sleep in their van, in their backyards, or on their couches, get drunk and pass out on their laps even. Of course, that’s just one anecdote. But it’s not what happened in the 1970s. Some of the punk bands did not take advantage of young teen girls. They treated us as music aficionados, people fleeing our parents, not as groupies.