Fleeing Reagan, Stealing from Museums, and Magic Mushrooms: Tuxedomoon's Long, Strange Trip

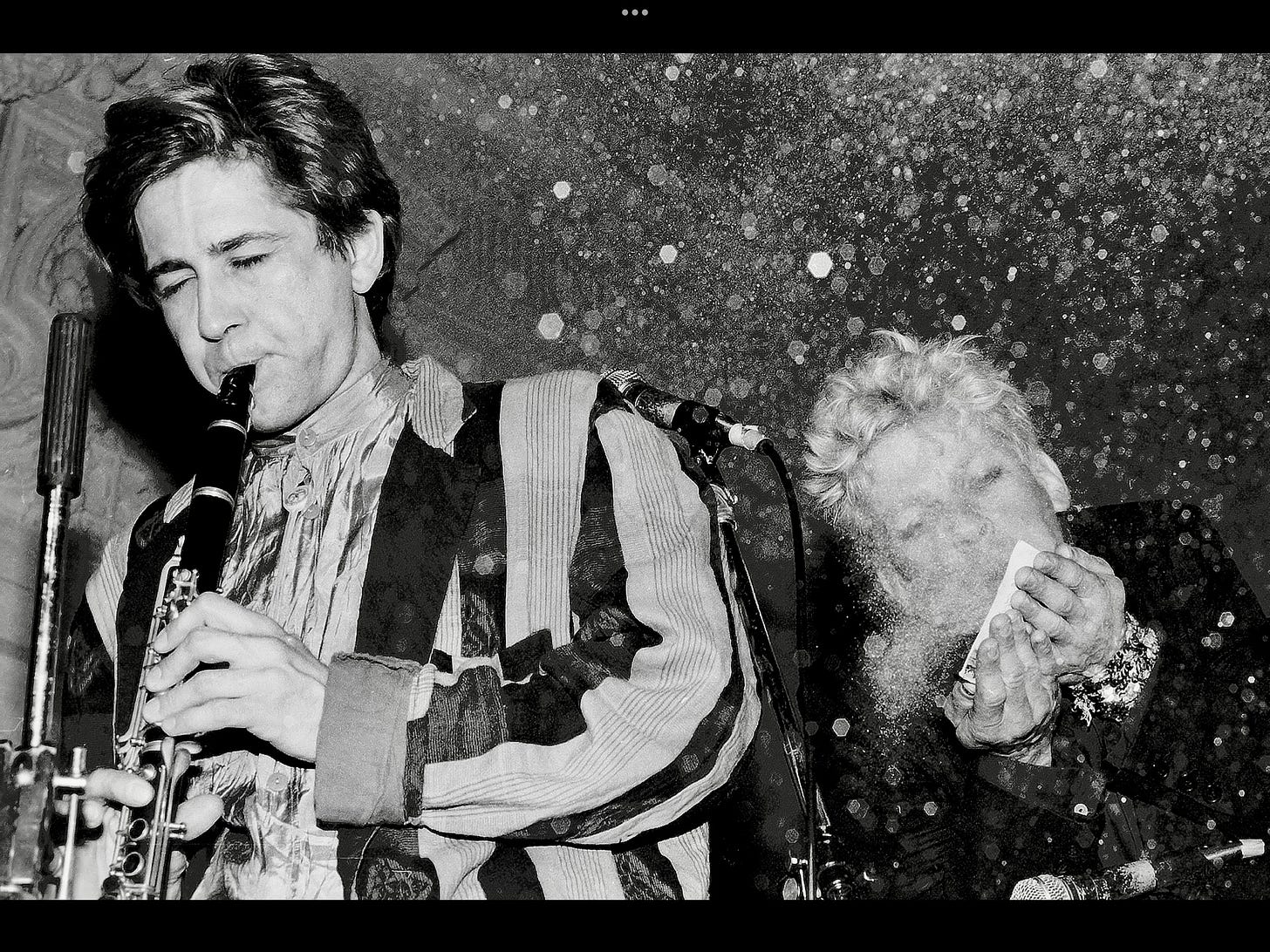

Tuxedomoon's co-founder, Steven Brown, left America 45 years ago—but he never faded away. Now he’s back with a thrillingly moody album and a gorgeous remaster of the band's 1981 classic "Desire."

Unless you were deep in the late-70s San Francisco underground, you might not know who Steven Brown is.

Even by the standards of the day, Tuxedomoon—the “electronic cabaret” band Brown co-founded in 1977—existed on the periphery, a shadowy group whose genre-blurring art seemed in moments to bend time itself. Was it debauched cabaret jazz? Corrosive No Wave? The soundtrack to some alt-universe Weimar Republic? No one could say for sure; like their shape-shifting music, the group itself seemed to exist everywhere and nowhere at once: San Francisco, New York, London and Brussels.

Besides Brown, Tuxedomoon’s mainsprings have at times included Blaine Reininger, Peter Principle, and Winston Tong—many of them well known figures in the art, music, film, fashion and design worlds. But if Steven Brown keeps a low profile, he’s far from idle. Residing now in Oaxaca, he still finds fervent audiences in Europe, Latin America and beyond. Known for his sonorous vocals and elegant instrumentation, he’s collaborated with theater, fashion, and film directors including Wim Wenders, Maurice Béjart, Thierry Smits and others. On an unconnected note, he was also partly responsible for setting in motion the chain of events that resulted in the remix of The Stooges’ epochal Raw Power, a tale told in exhaustive detail elsewhere.

I recently sat down with Steven Brown over Zoom to discuss his forthcoming album, In This Very World, Tuxedomoon’s recently reissued and remastered sophomore album, 1981’s Desire, and the experience of fleeing America for greener pastures.

Stealing From Museums

Dispatches From The Fringe: Your art seems to swirl conceptions of linear time. I hear very modern voices; I hear voices from a century or more ago: folk, electronic, avant jazz. Where does it all originate?

Brown: Winston [Tong] used to have a metaphor about going into museums and stealing everything. He said: “There’s nothing wrong with that!” You can steal from anybody and that’s okay, that’s accepted, that’s permitted, and so that’s what I do; that’s what Tuxedomoon did. The thing is, we try to make it less obvious.

I remember in San Francisco in the rehearsal studios, there’d be announcements on the bulletin board, bands looking for a “singer who sings like ____” or a “guitar player who plays like ____” and we were just like, horrified, you know? We’re trying to do new music here! We don’t want to sound like anybody. So that was rule number one: come with ideas, but don’t sound like anybody else. So when we started working on a piece and it started to drift too much towards Roxy Music or whatever, stop and twist it some more. So it’d be more ours, more unknown.

DFTF: Outside museums, what are some early influences of yours?

Brown: Well the cinema for sure, the combination of cinema and music, specifically Bernard Herrmann and films like Mysterious Island or Sinbad, the one with the dancing skeletons. You know, when the sorcerer throws these seeds in the ground, and skeletons pop out. And Ray Harryhausen was doing the stop-motion animation. It just blew me away, and I knew that’s what I wanted to do. But I never made it to film school. And Tuxedomoon kind of satisfied that need, because we had a filmmaker in the band, we did what we called “live movies” onstage, and that kept me quiet for a while.

DFTF: Everything you’re saying about cinema and the blurring of genres, it’s all right there in the video for “Panic In Detriot.” It’s a beautiful film and a beautiful take on the song. Why that specific Bowie song?

Brown: Oh, well, the connection with the White Panthers, and John Sinclair. I was a member of the White Panthers for a minute when I was at university. I always wondered what the hell [Bowie] was going on about. And then a few years ago, I read an interview with Iggy Pop where he mentioned that song, and yes: it was inspired by John Sinclair. According to Bowie he looked like Che Guevara, but I’m not so sure. And I thought it’d be funny to build on that, do a little homage to Bowie, but also Sinclair and that whole era.

You know, I went to Fred Hampton’s funeral, the head of the Black Panther Party in Chicago. I was, like, 15 or 16 years old, Jesse Jackson was there speaking. Since a pretty young age, I’ve been aware of all the shit going down, and I tried to be supportive of different movements and whatnot.

A white kid asked Huey Newton How can we support you? And he says, Start your own party. And so that’s sort of where the White Panthers came from. The Black Panthers were cultural but political, and the White Panthers were more cultural. You know, they were kind of goofy and hippie. John Sinclair was a big marijuana advocate, of course, and sex in the streets and art for free. It was a way to, in my mind, parallel what the Black Panthers were trying to do in the black community.

Mood Music

DFTF: Everything I hear in your music is less about reproducing or referencing a specific style than creating a specific mood. You’ve spoken before about some of your influences being dream-based. Can you speak to that?

Brown: That’s what I do—moods—but most of my moods are depressing! Wagner said music is the language of melancholy, and he’s right. I don’t know what happy music is. All music makes you…if it doesn’t make you sad, it at least takes you to another place that isn’t hardly ever happy. But that’s what I like.

DFTF: It reminds me of something Robyn Hitchcock wrote; something about hearing a piece of music (by Love? The Beach Boys?) and noting how certain artists seem to sense that “sadness is the shadow of beauty.” I thought that was such a simple and lovely way to crystallize it.

Brown: Yes, to be beautiful, something must contain some sadness in it. It’s like when you eat mushrooms, it’s like an ecstatic orgasmic effect. But the bottom line is, it’s very sad. You’re very sad and you get the feeling that the whole universe is based around the sadness.

You know, I’m in Oaxaca, not so far away from the town of Maria Sabina. [Sabina, a Mazatec shaman, was the first known person to allow Westerners to participate in the indigenous psilocybin ritual.] It’s medicine which I haven’t taken in years, but I cured myself of the flu once, I cured myself of intestinal parasites. This is medicine more than any kind of trippy thing. It’s an amazing story that very few people know about, and [Sabina] was just destroyed by the end of her life, feeling completely betrayed. She said “the magic is gone, the mushrooms aren’t speaking to me anymore” because of all the people that exploited her and all the hippies that came and all that.

DFTF: What was your own initiation into psychedelics? You wrote something to the effect of some kind of derangement influencing your writing.

Brown: I never was really into psychedelics outside of marijuana and hashish and opium. I don’t really remember when I took acid the first time…. Entering that state with the other musicians is a sort of portal into something else, into something that can’t otherwise be accessed. Derangement of the senses; the Rimbaud idea, Blaine [Reininger] talked about that a lot. But, you know, we didn’t take acid. Well, actually, Peter [Principle] took acid and played a concert, but not me.

A group of people playing together, just improvising, but at the same time searching for ideas together in a way that hours would go by and maybe nothing would happen, but you would get into a certain space for sure, with or without drugs, through improvisation.

I don’t like improvisation on stage in Tuxedomoon and myself. The improvisation stays in the rehearsal studio. We take ideas that we like and build on them, you know? I mean, this is a pretty common way of working, I think. But like jazz and, you know, endless solos and all that, I…it’s not for me, and that’s probably why I’m not a big fan of jazz.

Funny thing is now it’s huge here. People love it, improvisation. Almost every night there’s somebody doing this in the city, even here in Oaxaca. It’s more fun for the musicians than for the audience, I think. I don’t know, I can’t keep up with the times.

DFTF: Someone wrote something to the effect of “Tuxedomoon never had an anthem like ‘Transmission’ or ‘A Forest,’ and that’s a shame….”

Brown: We did! We did; it was called “No Tears.” Of course, for years we never played it! That’s another one of our idiosyncrasies, to be perverse. People want to hear it but we never played it, and that probably was beginning of our demise. But you know, repetition is the key to success. I mean, take The Allman Brothers: I saw a video of Greg playing the organ in 2003. I mean, he’s been playing that same song for 50 years, and it’s great. I love it but my god, I couldn’t do that. That’s why we didn’t get rich.

DFTF: So wait a minute, you don’t like jazz, but you like the Allmans?

Brown: [Laughs] Yeah, yeah. Oh, I like Miles Davis. I, you know, like certain jazz. I mean, Bitches Brew….that’s what turned me on to Miles Davis. From then on, I liked almost everything he did.

DFTF: The blending of genres?

Brown: The blending of genres, exactly. I mean, when he put a guitar effect on his trumpet, I think that was great, yeah.

Leaving America Behind

DFTF: I want to pause on a lyric of yours:

“The past is not over, the past is not past

I have no choice but to be

An enemy of my time, this faceless tyranny time

This fiendish time, this time of fiends.”

My understanding is that when Desire originally came out, you were trying to escape the Reagan Era. Can you talk about that at all?

Brown: Yeah, well, no, it wasn’t so much Reagan; it was San Francisco. You know, the Harvey Milk / George Moscone story. [They were] assassinated by an ex-policeman whose defense was, you know: He was a family man, and he was under a lot of stress. And this actually worked; he got a very light sentence. And then Dianne Feinstein came in as mayor, and we just knew something was really wrong. And so it was the end of San Francisco, as far as we were concerned.

That’s when we went to New York, and then to London, and then once we were in Europe on tour, we jokingly said: “If Reagan’s elected, we’re not going back!” And that’s what happened. We were fine in Europe, to be honest. It was much better for us, and so it wasn’t like we missed going back.

DFTF: That story of leaving America for more fertile fields in Europe, that’s the story of American popular music, to some extent.

Brown: You mean, like the Paris jazz scene jazz and all that? For sure, not only musicians, but…yes, it’s true. It is a tradition. And we were aware of that. It kind of felt good to be part of it in a completely unexpected way, you know.

DFTF: Did you ever think you’d return?

Brown: I never really thought about it, to be honest, and I know I won’t. I mean, it’s a drag. My partner is Mexican. He’s never been to the States, and he’s had a visa for like, 10 years. Never used it. He used it once to change planes in Washington to go to Europe. There’s one more year on his visa, but everybody says this is not the time to visit. I wouldn’t even think about it. I mean, I’ll go back when the revolution starts!

DFTF: But you’re playing two U.S. dates, right?

Brown: I’m playing at the Stork Club in Oakland, California on the 23rd, and then in LA on the 25th of January at Zebulon.

Music and DMT

DFTF: One thing I find fascinating about your work is that you’re inhabiting all these sonic spaces at once, a specific vibe that people have picked up on for the last…going on 40 or 50 years now.

Brown: Well, what’s fascinating is how we hear sound. It’s just molecules of gases bouncing around. You know, the speaker cone moves the air, and the air turns into Debussy or the Beatles. I mean, it’s just incredible.

I was just reading Jacobo Grinberg, who was a Mexican physicist who disappeared in 1994 under mysterious circumstances. And he went around and interviewed all these shamans in Mexico. Anyway, he says: You’re sitting in a room, you see the chair and the table, and the space between the chair and the table is empty, right? No, there’s a whole matrix there that a shaman can connect with. In particular, this one who would do these psychic operations and remove organs from people and just grab an organ from the the air and put a new organ in a body. Shamans can see and access this and we cannot, but that’s what sound is. I mean, we don’t see anything there, but there’s molecules there, and when you turn the stereo on, those molecules start to move, and that makes music. It just sounds silly, but it blows my mind.

DFTF: Are you familiar with DMT?

Brown: I don’t know if I’ve ever tried that one.

DFTF: It’s eerie how many people, myself included, have roughly the same experience, which is that it’s very brief—maybe 5 or 10 minutes—but you are transported to some alien landscape that’s somewhat cartoonish, with solid colors and bold lines, and alien surgeons are performing some sort of operation on you. It’s not painful, it’s not threatening, but you’ve just gone to this other dimension where these surgeons are doing something to or for you, and then you return here to Earth. That sounds very much like what you’re describing.

Brown: Have you done it more than once?

DFTF: I have, and it’s always the same, thematically.

Brown: Didn’t Terence McKenna talk about that?

DFTF: Absolutely, that was sort of his trip, so to speak.

Brown: I’ll have to try it.

DFTF: If nothing else, it’s brief!

Brown: Right, right. That’s good!