Give Me a Sign: What a Marquee Across the Street Taught Me About Failure

The night of my tiny book launch, I was already jittery. Then I saw the marquee: My punk-rock nemesis was having their own book party, in a giant theater, literally across the street.

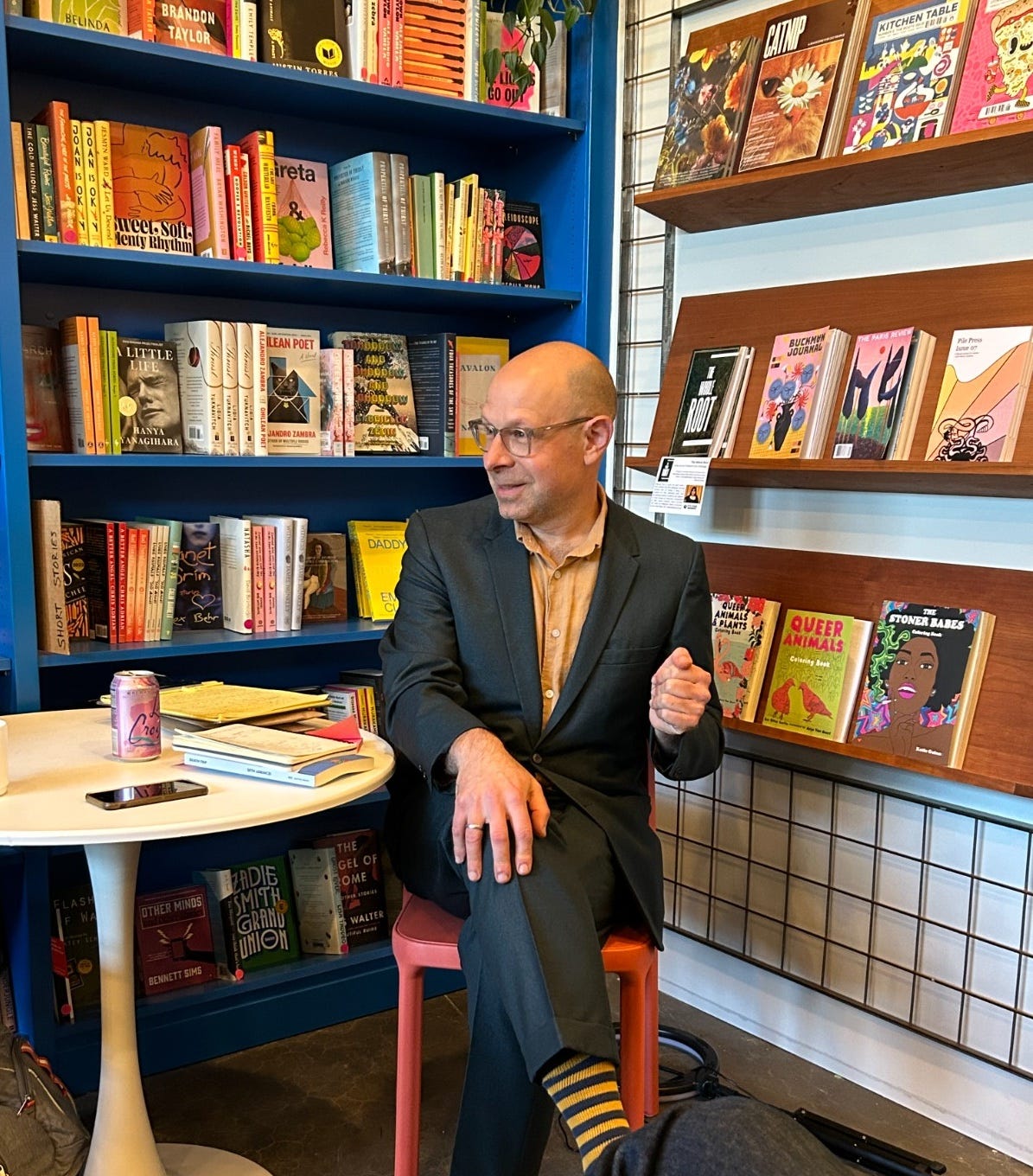

Yanking the parking brake and keying off the engine, I sat for a long moment, struggling to quell my nerves. After seven long years of writing, ripping up, and revising, it was hard to believe my book launch had finally arrived. The event was to be held at a little bookstore in Portland’s Buckman neighborhood called Up Up Books. It’s small but artful, boasting—in the owner’s words—a “kick-ass poetry section.” I prayed, for the hundredth time, that anyone would actually show up.

This wasn’t mere paranoia (though, of course, that’s exactly the sort of thing a paranoiac would say). What I mean is that in the literary world, my book was the smallest of small potatoes, published by a fledgling micro-press with zero marketing budget.

I’d wanted it to be different, at least at first. I’d done all the things, queried dozens of agents. But the few who responded said more or less the same thing: “This is good, but I wouldn’t know what to do with it.” And so I’d taken matters into my own hands, forming a publishing collective with a few of my writing partners. Just like in my punk days. But that meant no promotion, no high-powered ad campaigns. It was, for better or worse, all down to me. And in an hour, give or take, I’d learn whether or not I’d succeeded.

There wasn’t really much setting up to do, given the size of the bookstore—Up Up Books holds 40 people, if they’re willing to get up close and personal. And so I took a walk around the block to steady myself. On the return leg, approaching the bookstore opposite from where I’d parked, I spotted the marquee for Revolution Hall, the 850-seat venue directly across the street. Wonder who’s playing tonight, I thought as the letters came into focus. Then I saw the name, and I stopped dead in my tracks.

The event across the street from my book launch was also a book launch, and it was for someone I actually knew. I’d briefly counted them as a friend, back in the D.C. punk scene. Before they became my nemesis.

For a long moment I stood there, willing the letters to rearrange themselves. If I’d needed a signal from the cosmos, there it was: a figurative (and literal) sign staring me right in the face: You failed.

In 1990 I lived in Mt. Pleasant, the very epicenter of the D.C. punk scene.

A modest neighborhood of immigrants and civil servants, Mt. Pleasant is bordered on two sides by Rock Creek Park, giving it the feel of a self-sustaining citadel. The rest of the city was violent, and visibly failing. That was the year Washington became the “murder capital,” boasting at least a killing a day—often more. I was never seriously threatened, though I was shaken down by parking enforcers, and once had guns pointed at my face by a couple of undercover cops.

But it isn’t the threat of violence I remember; it’s the nights. D.C. was then still very much a Southern city, and once the heat of the day faded time seemed to slow to a crawl. With the windows cracked against D.C.’s notorious humidity—no one had A.C.—a riot of sounds filtered in: Back-alley motorcycle mechanics, endless band rehearsals, laughter and shouting down the block. Sometimes, as dawn tiptoed through the neighborhood, I’d hear the unearthly howls of the gibbons in the National Zoo just a few blocks away.

I was 19 years old in 1990, and I lived and breathed music. Everyone did: my roommates all dressed like ‘50s hoods and called themselves Nation of Ulysses. They were incendiary. Half of Fugazi lived a few blocks away. Special K, Fire Party, Holy Rollers; everyone was in a band. Everyone, that is, except me.

My high-school band had broken up a couple of years before; I wouldn’t join my next for another year. Desperate for an identity and a sense of purpose, I was painfully insecure. But my thwarted ambition wasn’t something I could talk about—at least, not in plain English. Even wanting something so nakedly felt somehow shameful, and so I quashed my simmering frustration as best I could.

I had a bad case of punk damage.

“Punk damage” wasn’t a phrase people used back then—though I’d bet anyone who was there knows exactly what I mean. It’s the belief that ambition is toxic, that wanting to “make it” is anti-punk, anti-scene, maybe even anti-human. Behind it, of course, is fear: The terror of asking for approval from a world that’s already rejected us before.

Maybe that’s what made my erstwhile friend so compelling.

We bonded quickly, spending sweltering nights spinning records, driving near-empty freeways to suburban pool halls. But mostly we talked, because it was free. About the scene, about obscure bands only we’d heard of, about which renditions of songs were better—the singles or the album versions?

It was a romantic friendship, though no actual romance occurred. Maybe that’s why the inevitable breakup stung so badly. In contrast with my friend—fearless, fairly dripping with charisma—I was the perfect sidekick and dupe. They chatted up all the right people and name-dropped the right bands, while I could barely look up from my shoes. After they dropped me—with unflinching, reflexive cruelty—they poisoned my most treasured friendship, too; it took a full decade to clean up the fallout. What I see now is how my onetime friend played on my hunger for recognition—and how fearful they were of exposing their own.

I was still staring at the sign across the street, bittersweet memories swirling within me like a flash flood. All these years later, my onetime friend had triumphed, their book launch mere feet away from mine, about to kick it to the curb. I opened my phone and looked up their Instagram, just to be sure. Yup, it was them. And if social media followings are any metric, they are approximately 121.08 times more popular than I am.

Then a tiny dam gave way inside, and I began to laugh. The perfection of it all, the sheer hilarity. Could there be any clearer evidence of a playful—and thus loving—universe?

Thank you, Spirit.

Publishing a book is a tender act.

If you’ve done your job well, you’ll share something intimate and vulnerable—with no guarantee anyone else will care, much less read it. But I’m a punk, after all, and I’d learned something of value all those dreamy nights past. Punk wasn’t the fear of failure. It was the certainty of failure. What was left but to embrace the fruitless and the beautiful? Punk told us the past didn’t matter and the future was unwritten. I’d waited my whole life for the world to come find me, and now it was getting late. I could be grateful, or I could be bitter. It was no one’s choice but my own.

I stole one last glance at the marquee, thanking the impeccable timing of the cosmos. Then I walked back into the little bookstore, faced the crowd of friends and well-wishers who’d gathered there, and had the night of my life.

For anyone as flustered as I am about the lack of transparency regarding Seth's nemesis, perhaps a look at the entirety of the piece will shift the perspective prism. If we were to pair the "Spirit" of the cosmos with the fact that an existing Instagram account hosts pertinent information, what we're left with is the foundation for a quick research project... a punk rock scavenger hunt, so to speak. He's already given us the story for free, the least we can do is work for the name. And, if I find it... I'm going to keep it to myself!

At first, I was frustrated with you not mentioning who your nemesis is and then I realized how exactly punk rock is to not name drop someone who is that many times more popular than you on a social media app. Compelling writing as always.