Going on a “Death Trip”: How I Unearthed My Buried Family Stories, Found My People, and Learned to Write

When I started my memoir I was lost, in more ways than one. Seven long years later, my life is very different: I know where I came from, I have a strong community, and I can even call myself a writer.

Years ago, when I was still struggling to figure out how to tell this story, one of my writing partners shared a tip:

By the end of the first page, we should know that the problem is. What it is the protagonist lacks, and maybe a hint as to how they might find it.

That turned out to be better advice than I could have realized. As I quickly learned, my problem wasn’t just a literary one. I needed to unearth my family’s most deeply buried stories, and I suspected that the slender clues I had access to—in my father’s memoirs—weren’t entirely trustworthy.

Oh, and I needed to learn how to write.

Piece of cake, right?

Now, as I prepare to send the finished book out into the world (the official launch is Tuesday, May 21) I’m looking back at where I started, and what I had to overcome—as a fledgling writer and, more importantly, as a person—to get here.

Writing Into Life: How Solving Literary Problems Solved Life Problems, Too

In a nutshell, the point of the book is that ancestral trauma isn’t ancient history, but that it plays a far more active role in our lives than many of us suspect. In my case, I grew up knowing surprisingly little about my family backstory. It wasn’t until middle age, when my entire life seemed to be dissolving—my marriage in crisis and my career a disaster—that I got the hint that maybe the two were connected.

As I’d learn, those unexamined threads extended into the darkest recesses of my family history. But untangling them wasn’t even the first task. As I began working on the book in earnest, I recognized that I faced three interlocking problems:

I didn’t know my backstory. I had some source material to work with: My father’s memoirs had sat in a filing cabinet since his death, twenty years before. But they spanned barely twenty-five pages, ending with puzzling suddenness during the Battle of Budapest. They didn’t so much answer questions as tell me of how little I really knew.

I didn’t know if I could trust what little documentation I had. After my father’s death, I’d learned that he’d burnished or obscured certain parts of his backstory (I wrote a short essay about this, published in The Keepthings). Though the specifics seemed inconsequential it left room for doubt, and it told me there was a story behind the story.

I didn’t know how to write. When I began this book, I’d written exactly one piece of personal writing—an essay on my father’s death, twenty years before. I had no idea what I was doing, only that I had to do it.

So on top of the narrative problem—how does the story move convincingly from Points A to Z?—I had three real-life problems to solve. Here’s how I did it.

Chasing Down Leads: Hitting the Books, Picking Up the Phone

Even though I wasn’t sure if I could trust my father’s recollections, they alerted me to a belated—but crucial—realization: That I had a backstory. I knew next to nothing about my Hungarian family, but as I traced their story, I recognized that it intersected with some of the most wrenching chapters of the 20th century: The Holocaust, the World Wars, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism it helped enable.

This stage was incredibly exciting. Working off the tiny clues embedded in my father’s memoirs, I began researching historical moments I’d known nothing about, like the Alpine Front of the First World War—where my grandfather battled an environment so brutal and unforgiving it beggars the imagination—and the war’s aftermath.

From my untutored, American perspective, the war ended and everything went back to normal. What I learned instead was that in much of Central Europe, the end of the conflict unleashed waves of mass violence, starvation, and hyperinflation—all set against the looming horror of the influenza epidemic. And that my grandparents, who’d played a large role in my own upbringing, had entered adulthood against this unbelievably uncertain and threatening backdrop. What had it done to them?

Having essentially forgotten I even had a Hungarian family, I began reaching out to them. These reconnections were touching, and they sent new pieces of evidence trickling in. Many were in the form of photographs, both of my young grandfather at war and of the world my aunt and father had been born into: The Hungary of a century ago, a place now so distant it’s hard to even imagine.

As these concrete images added to the reams of historical evidence I was absorbing, a strange thing began to happen. The past seemed to come alive inside me, igniting long-buried tendrils of memory and meaning. As far back as I could trace, my ancestors’ experience had been colored by loss, trauma, and uncertainty. As Jews in an increasingly antisemitic world, their footing was far more tenuous than I’d imagined, and I began to wonder what it was doing to me—right here and right now.

That’s when I realized, belatedly, that there was someone I could actually ask about it all: My Aunt Csupi, now in her mid-90s and living in the impeccable bowels of a Swiss nursing home.

Csupi is a complicated figure in the book—as she was in real life (she died, of COVID-19, in 2022). Bright, acerbic, given to scabrous outbursts of racism and snobbery, she was exasperating and infuriating, and I’d let the connection drop years before. But she was also the last living link to a fast-vanishing time, and I knew that if I could brave the rapids of her native cattiness, I’d learn far more than what was contained in the history books. As we began speaking regularly, I felt as though I were falling through a trapdoor.

But I’ll save that for the book.

Hits and Misses: Writing Partners and Agents

As I began writing in earnest, I realized that I had to build my skills—and fast. And so I asked the most accomplished writer I knew—Ben Parzybok, author of Couch and Sherwood Nation—if he’d start a writing group with me. Incredibly, he agreed, and six years and several lineup changes later, we’re still going strong.

I can’t overstate what a big deal this was. For someone who grew up without the traditional structures of college and a career—I’m self-taught in most regards—having a dedicated support system centered around critical feedback and honest reflection is huge.

And as someone who came of age in the punk scene, it reminded me of what I already knew: That as creatives we have all the resources we need, right here in our own communities. I urge anyone even slightly interested in the craft of writing to form a group of their own. It will reward you far more than you can imagine.

The same goes for publishing. I’ll be transparent here: I very much wanted an agent and a traditional publisher. I wanted the stamp of approval, someone to come in and say “You did a good job!” and then grant me the acclaim I felt a publishing deal would give me. (This is, coincidentally or not, the other major life problem the book addresses: Why don’t I feel like I belong to my life?)

But that’s not what happened. While a few agents expressed interest and said kind things about my writing, none offered me representation.“We wouldn’t know what to do with this,” was the most common response, or—even more dispiriting—some were already working with similar manuscripts.

I felt like I’d missed the boat, and that now there was no way my book would make it into the world. That’s when another of my writing partners challenged me. “You grew up in the punk scene,” she said. “So you know there’s no reason not to do this ourselves.” Soon we had another partner, and thus Spiral Path Collective was born.

The “us” part was critical. Up till now, resigning myself to self-publishing felt like the worst kind of defeat imaginable. But having partners changed all that in the blink of an eye. Now I had allies and support. And I had complete creative control—meaning that my book would read (and look) exactly how I wanted it, and that I could share it and its message on my terms, not anyone else’s. Now I could say—with total, sometimes painful honesty—that I’d chosen this path with an open heart.

Trust-Fall: Letting Go and Accepting

There’s one final aspect of this book I have to talk about. As a writer, I thought I was in charge of the story. But as I scrabbled through what I was uncovering—a box of jigsaw pieces with no picture to orient towards—I found the book was writing me as much as I was writing it. I had to learn how to surrender, to let go the reins when the narrative took unexpected turns, and I learned how to trust the answers would come—even when they seemed farther away than ever.

The climax of the writing process—and of the book itself—was a month-long trip to Hungary, now exactly five years ago. Nothing about it made sense: I was barely earning enough money as it was, and I feared it would be an expensive and pointless quest.

What was I hoping to find there? My family’s now-elderly former neighbors, who’d fill me in on all the missing plot points and details? A historical plaque reading “In 1944, the Lorinczi family moved from ______ Street to ______ Street and hid in this very cellar!”

No. But once I accepted I had to at least try, I faced the challenge as squarely as I could. Once I let go of the need for hard evidence and opened myself up to the fractal, ambiguous, even irrational clues floating all around me like the cottonwood blooms that waft through Budapest each spring, I learned far, far more about my family’s ordeal than I ever believed possible.

But that wasn’t all. My younger sister joined me for the first week, and the chance to reconnect outside the bonds of family life and daily routine was more profound than I could’ve imagined. It echoes still, and has changed how we relate to one another for the better. I also reconnected with my Hungarian family and friends on a far deeper and more meaningful way than I ever had before. In Hungary—challenging as the trip sometimes was—I found I could rest in the care and goodwill of people who’d loved me even before I was born.

Epilogue: Launch Day

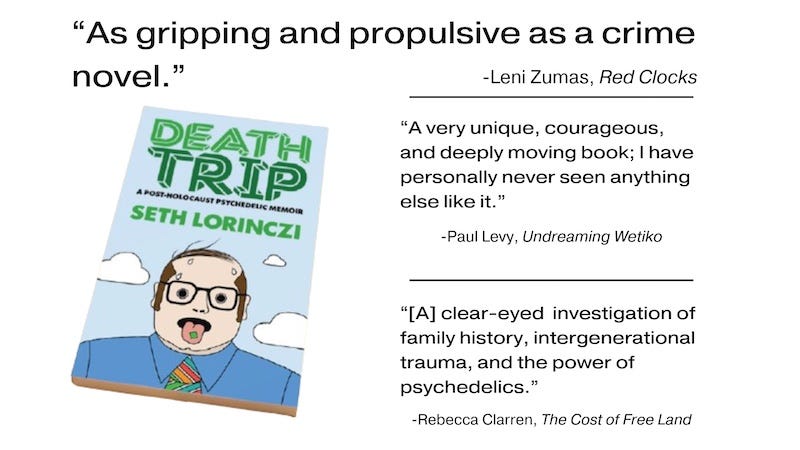

There’s more to say, of course. But as the emails and videos from early readers come in, and the marketplace seems to be responding positively—the book has spent the last week at or near #1 on Amazon’s “Jewish Biographies & Memoirs” and “Family and Personal Growth” categories—I’m grateful beyond belief that it’s touching others:

“Lorinczi's skill at the sentence level is apparent, because I would find myself rereading sentences throughout just for the pleasure of watching the phrases turn.” -F.G.

“Riveting, heart wrenching, and a pillar of hope to keep showing up. The biggest gift is that the author gives you a real account of what it looks like to go through this journey of healing and self discovery.” -A.G.

“Anyone who has had parents, or hasn’t had parents, who has relationship, struggled or failed in relationship; anyone thinking of turning over the log should read this book!” -D.T.

One final—no, really!—word. When I was preparing “Death Trip” for publication, I spoke with a seasoned editor I’m friendly with. At the time, I was feeling stressed about the book’s low prospects of commercial success. She shrugged and asked: “Did writing it change you?”

I didn’t have to think long about that: “Yes, absolutely!”

“Well, there you are.”

Indeed. There I am. Thank you so much for following along on this journey. I’m grateful beyond words.

We share some friends in common a few who came to see you on the Berkeley leg of your tour. They witnessed you on stage like, “Who is this guy!?”. This guy is a WRITER, finally taking the shape he was always meant to. As well I’ve heard reports of not being able to put the book down. “No really, I keep postponing sleep to keep reading” . Seth, I’m looking forward to not being able to put your book down. Ordering posthaste.

My late mother was my muse in my first book. I definitely relate to reaching out to someone who was the last living link to my family's past.