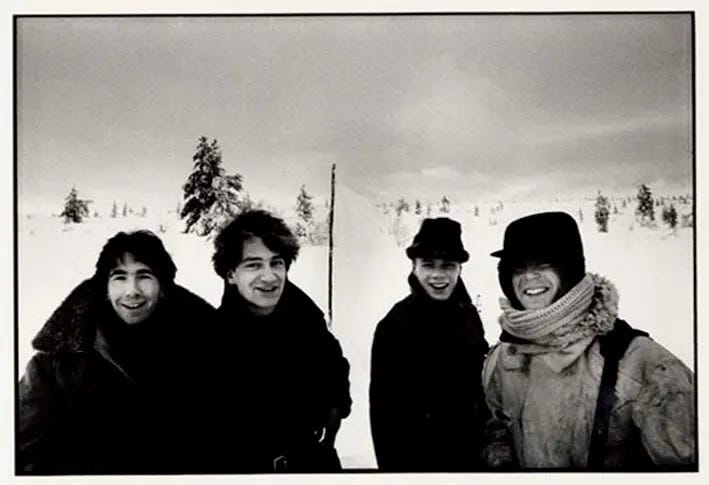

Happy “New Year’s Day”! How U2 Created Their Breakout Hit

Love them or loathe them, U2 never sounded more urgent. But until nearly the moment Bono stepped up to the mic, he didn’t even know what the song was about.

Chalk it up to my naturally sour disposition, but the current wave of ‘80s nostalgia leaves me cold.

I was 12 years old in 1983, and where I grew up—in Washington, D.C.—the ’80’s weren’t exactly joyful. The Cold War felt like a physical weight, as palpable as the city’s notorious humidity. On top of this, District was (and still largely is) a heavily segregated city. Though I possessed the political consciousness of a cocktail onion, the sense that things were badly wrong—and that no one would even admit it—troubled me deeply.

The only thing that seemed to help was music, but therein lay the rub. Nothing on the radio mirrored my experience, or felt remotely real and authentic. The airwaves were awash in a sea of saccharine: The doggone girl is mine, insisted Michael and Sir Paul; Toto was stranded in Africa; Don Henley aired his dirty laundry, again and again and again. Everything sounded so processed and fake. Things were getting so desperate that I seriously contemplated wearing a fedora. You know, to give me some edge.

Then came “New Year’s Day.”

In 1983 U2 were hardly an underground band, but that song tapped into something edgy and essential. Riding on a hungry and relentless bass line it was the sound that was so unprecedented. The music was honest and real, seeming like something even I could do. Like so much of the music we absorb in adolescence it felt deeply personal, expressing something about the world—about myself—that rang ineffably true. And like other bass-led burners—Joy Division’s “Transmission”; Fugazi’s “Waiting Room”; Grandmaster Flash’s “White Lines”—“New Year’s Day” sounds somehow as if it’s always been there, a monolith carved into a cliff face just waiting for us to discover it.

But like many eventual classics, U2’s breakout hit had a long and tortured gestation and it could’ve gone any number of ways. Here’s how it really went down.

Hero Worship: The Joy Division Connection

In 1982, U2 were at a precipice. While 1980’s Boy had been a moderate commercial and strong critical success, its follow-up October was seen as a step sideways: Darker, more muted and inwards. Behind the scenes, the band’s very future hung by a thread. Three of the band members—singer Bono, guitarist the Edge, and drummer Larry Mullen Jr.—were involved in a Charismatic Christian group called the Shalom Fellowship. Increasingly withdrawn and alienated from their crew, they were questioning the very pursuit of stardom. During the making of October, Bono stormed into the control room and proclaimed: “The Second Coming is going to happen and it’s going to happen within the next ten years!” After he left, producer Steve Lillywhite deadpanned: “That idiot thinks he is the Second Coming!”

Though he’ll always be associated with U2, Lillywhite wasn’t the band’s first choice. After the band signed to Island Records, they’d asked Joy Division producer Martin Hannett to oversee their debut. In March of 1980 they paid him a visit as Joy Division was recording “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” In hindsight, it was a spiritual passing of the torch. Writing about the event decades later, Bono recalled his fascination with the LPs strewn about the studio: “Who would listen to Frank Sinatra and Kraftwerk and Bartók and Motown and the Stooges at the same time?”

But Hannett’s involvement with U2 wasn’t particularly successful. When the legendarily mercurial engineer went to Dublin to record U2’s next single, “Eleven O’Clock Tick Tock,” his oddities and excesses alienated the band. Believing 3am was “the most creative time” he pulled serial all-nighters, guzzling cough syrup and smoking anything he could find. After he fell backwards off his chair and exclaimed “Jesus Christ! I’ve just hallucinated a gherkin!” the largely teetotaling band were, in the words of engineer Kevin Moloney, thoroughly freaked out.

It’s fascinating to imagine U2 recast as Joy Division’s heirs, but the results are—to my ears at least—underwhelming. Hannett created an endlessly captivating soundscape for the Manchester band, entombing them in sheets of sonic ice in which Ian Curtis’ limitations as a singer work in the band’s favor. But in this polar wilderness U2 just sounds stifled and small—a lesson in the pitfalls of chasing one’s heroes. After Hannett withdrew following Ian Curtis’ suicide that May, the band went with Lillywhite instead.

Compared with his predecessor, Steve Lillywhite was a paragon of solidity and focus, working fast and instinctually and pushing the band to embrace the urgency of their live performances. By the time they were ready to start recording War, the band and their producer were in lockstep. All that remained was to capture their fire.

The Sound of a Stone-Walled Room

“New Year’s Day” began as a soundtrack jam. Adam Clayton, hunting out the chords to Visage’s “Fade to Grey,” stumbled upon what would become his most iconic bass line. It’s a testament to his understated genius that in his hands, such a lightweight inspiration—sorry, Visage—became something so propulsive and essential.

Then there was the sound. It’s ironic that Steve Lillywhite—who’d worked with Peter Gabriel to craft the gated reverb drum sound that would largely define the ‘80s—went the opposite direction here, creating a thrillingly live drum sound that captures the excitement of standing in the room with the band. To achieve that “clattery” effect, Lillywhite tracked drummer Larry Mullen’s kit in Windmill Lane’s reception area, a low-ceilinged room with a tiled floor and four-foot-thick stone walls. This meant that the band—forbidden from disconnecting the telephone—had to wait till the daytime staff went home and pray no one would call during takes.

It’s hard to think of a single person who’s expanded the sonic palette of rock more than the Edge. Already distancing himself from the stacked Electro-Harmonix Memory Man delays that’d shaped his earlier sound, now he began to create ever vaster soundscapes using multiple Vox AC30s amps in parallel, each at different settings and recorded through multiple mics. Seemingly overnight, rock become more expansive, more eerie, more willing to hang out in the ether. By contrast, the keyboard part—played on a Yamaha CP-70, a hybrid acoustic/electric instrument—sounds plangent and direct, though like the guitars it too was sent through an analog delay chain.

If the rest of “New Year’s Day” came together more or less organically, the lyrics were a different story. Originally begun as a love song during Bono’s Jamaican honeymoon with Ali Hewson, the words had for months refused to come into focus. The singer—notorious for his reluctance to write out lyrics beforehand—preferred to take a spontaneous and improvisational approach. The lyrics may be ambiguous, but they’re hardly ambivalent: A mix of resignation, determination, and angst quite unlike anything else on the radio at the time:

Under a blood red sky

A crowd has gathered, black and white

Arms entwined, the chosen few

The newspaper says, says

Say it’s true, it’s true

And we can break through

Though torn in two, we can be one.

Incredibly, it was only after the song had been tracked that it gained its deepest resonance. The story of Poland’s Solidarity movement was a major news story that year. Its leader, Lech Walesa, had been imprisoned since December 1981, when the Polish People’s Republic declared martial law and outlawed the trade union.

“Subconsciously I must have been thinking about Lech Walesa being interned and his wife not being allowed to see him. Then, when we’d recorded the song, they announced that martial law would be lifted in Poland on New Year’s Day. Incredible.” -Bono, in a 2012 interview

Move Fast

Given where “New Year’s Day” would eventually take U2, it’s astonishing how quickly it came together. Recollecting in a 2013 interview, Lillywhite estimates it took him all of 15 minutes to mix the song. Still, its potential wasn’t clear to anyone in the room. According to Lillywhite:

“It’s funny, we didn’t think of it as a single. It was one of the young interns in the studio who first said to me, ‘That song is brilliant!’ And we all went: ‘Oh, really?’”

Yes, really. “New Year’s Day” would become U2’s first UK top ten and their first American hit, peaking at #53 on the Billboard Hot 100 in April of 1983. Soon U2 would be everyone’s band, giving me no choice but to quietly untack their poster from my bedroom wall and pretend we’d never met. But though our paths wouldn’t cross again, U2 opened a door for me, a major one. The imprint of “New Year’s Day”—the relentless bass, the questing piano, the delicious crack of the snare—runs deep still. Love them or loathe them, U2 never sounded more urgent and alive.

This is one of those times where my age and experience get in the way of me taking other people's writing at its intended value. I'm not the audience.

I was 25 in 1983. I worked at Island at the time; my boss signed U2. The music that put U2 on our radar and their earnest early live shows were SPECTACULAR. I wish all of you could have seen and heard all that. Except then you'd be over 65, like me....

I was a genuine U2 fan fir their first three albums, but got off the train after 1) being bored to tears by most of The Unforgettable Fire, and 2) seeing them on that tour and realizing that Bono was a pompous knob. This song still really does hold up, though.