Heartbreak, Scandal & Soul: How Ed Cobb Brought Angst and Grit to Pop

If you were a music-obsessed kid scanning the airwaves for signs of life, songs like “Tainted Love,” “Every Little Bit Hurts” & “Dirty Water” gave you hope. Believe it or not, one man wrote them all.

Do you remember the first time a song seemed to speak to you—and you alone?

In the early ‘80s, when I discovered the first wave of punk bands, it felt like a key in a lock: As the sounds of the early Clash, Dead Boys, and Buzzcocks filtered through the headphones of my knockoff Walkman, I felt seen, and it gave me hope. Finally, here was music that expressed just how confused and angsty I felt inside.

But a few years later, when my hipper friends turned me on to the sounds of even more obscure ‘60s groups such as the Music Machine, Chocolate Watchband, and Standells, I recognized the through lines to the newer music I’d been lapping up. Maybe punk’s “Year Zero” hadn’t actually been 1977, but 1966—or even 1955. The sounds may have changed, but the attitude beaming through the decades was fully intact.

There was another thing. As I read and reread back-jacket liner notes, hoping to glean some clue as to how this fierce, hard-charging music had been made—let alone survived to be reissued—one name seemed to pop up again and again: Ed Cobb.

Never heard of him? I can’t blame you. Even those versed in the more obscure byways of rock and roll would be hard-pressed to name what he did. But Cobb left his mark all right, and you could argue that all fans of edgy, driving music today owe him a small debt of gratitude.

In the Beginning: From the Four Preps to “Tainted Love”

Ed Cobb was born in South Pasadena, California, on February 25th, 1938. Little is known about his early life, though one snippet—that as a kid, he’d been exposed to gospel in a black Baptist church that he and future bandmate Bruce Belland would visit with Belland’s preacher father—hints at his eventual musical path.

A naturally gifted musician and singer, Cobb first rose to prominence as one of the Four Preps, a white doo wop group who found their greatest chart successes with "26 Miles (Santa Catalina)” and “Big Man,” both in 1958. The group also featured Glen Larson, whose name should be familiar to anyone who grew up on ’80s-vintage television. Larson masterminded Battlestar Galactica, Magnum, P.I., Knight Rider and similarly weighty contributions.

Safe, clean, and family-friendly, The Preps didn’t give much hint as to where Cobb’s musical predilections would take him. But early on, he began gravitating towards songwriting and production. And in stark contrast with the Preps’ squeaky-clean material, many of Cobb’s compositions tended to be hard-driving soul and R&B numbers. One was a song he wrote for Gloria Jones called “Tainted Love.” It didn’t make much of an impact in its first two iterations, but on its third try it became a record-breaking smash, hitting #1 in 17 countries.

Of course, being close and regular readers of Dispatches From the Fringe, you already know that. What you may not know is that this was hardly the end of Ed Cobb’s story, not by a long shot. A couple of years earlier, in 1962, Cobb had written the magisterial ballad “Every Little Bit Hurts,” which a 16-year-old Brenda Holloway recorded as a demo for Del-Fi Records, a Hollywood indie who’d scored hits with the late Richie Valens.

After signing with Motown in 1964, Holloway rerecorded a more polished version, which made it to #13 on the Billboard Top 100. Like the original version of “Tainted Love,” “Every Little Bit Hurts” found even greater success in its afterlife, being covered by Spencer Davis, George Clinton, the Clash, the Jam, Alicia Keys and—in a particularly compelling version—the Small Faces, among many, many others.

If Cobb had stopped there, having penned both a worldwide smash hit—albeit one some 25 years in the future—and a beloved soul / R&B standard, he’d have secured at least a small place in pop music history. But it’s what he did next that puts such an odd and compelling twist on the story.

“Dirty Water” and “Good Guys”

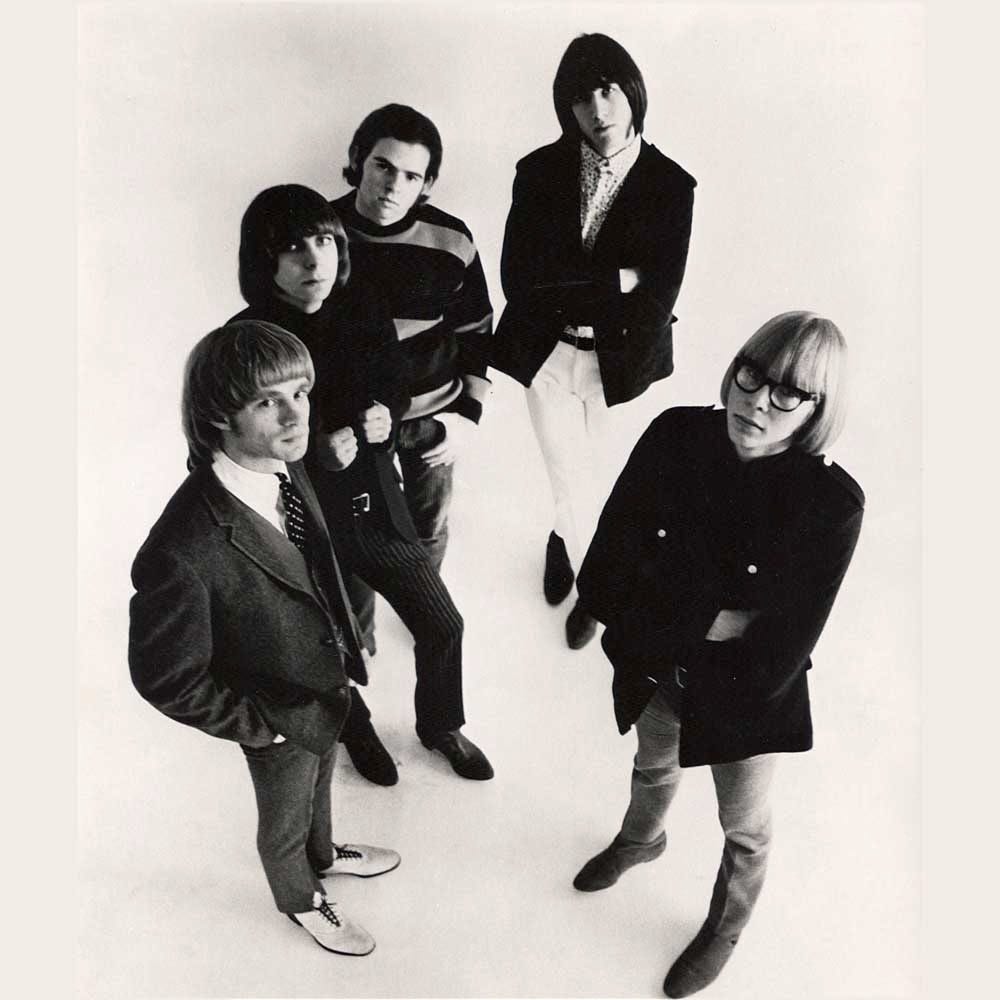

By 1965 Ed Cobb was a staff producer at Tower, an imprint of Capitol Records, and the Standells were a middling white R&B band playing rote versions of other people’s hits (“Money,” “Bony Moronie,” “Louie Louie”) and going nowhere fast, despite the participation of drummer (and eventually lead singer) Dick Dodd, a former Mouseketeer.

After signing with Tower the band were placed with Cobb, who was drawn to the group’s latent edge. He gave them a couple of harder-sounding songs to see if they could come up with something compelling.

The first was called “Dirty Water.” Supposedly written after Cobb was mugged on a visit to Boston, it’s a strange but propulsive blues rocker, made all the more so by the band’s ad-libbed interjections (“I’m gonna tell you a big fat story, baby!”). In early 1966 it went to #11 on the Billboard Top 100, earning the band an opening slot for the Rolling Stones summer tour that year.

“Dirty Water” may have brought a brash, proto-punk sound to the airwaves, but it was the Standells’ next release—“Sometimes Good Guys Don’t Wear White,” also by Cobb—that sealed the deal. A stomping kiss-off to the emptiness of polite appearances, it was arguably this song that planted the band’s stake in the ground.

Even if the band’s bad-boy image was largely hot air, “Good Guys” flippant message—and its grinding, cowbell-heavy clank—resonated with a new generation of ne'er-do-wells. Some, like Swedish revivalists the Nomads, were merely conforming to type. Others, like the pioneering Washington, D.C. hardcore band Minor Threat, put their own, unexpected spin on the song.

Despite helming Minor Threat and Fugazi—two bands not generally associated with the sounds of the ‘60s—Ian MacKaye is a serious student of garage rock. And he first learned “Good Guys” not from the Standells, but from the Cramps—an early and major influence on D.C. hardcore, despite the seeming incongruities. When Minor Threat decided to cover the song, the band was in the throes of a terminal identity crisis. In MacKaye’s words:

“(‘Good Guys’) was challenging for me, cause the singing’s so hard. At that time, we were going through a lot of drama about the direction of the music. The band really wanted to ‘progress,’ while I wanted to ‘evolve.’ Members of the band—maybe all of them—had become really enchanted with U2. But I couldn’t sing to it. It didn’t speak to me as music. It was at that time this song (‘Good Guys’) came in, and this was garagey enough, and I knew the melody, so I knew roughly what to do.”

As for the Standells, they would never again approach the chart success of “Dirty Water,” though they made a few waves with 1967’s leering “Try It,” which was banned for its “suggestive” lyrics—though it should’ve been censured for just being date-rapey and vile. But there’s one more chapter in Ed Cobb’s saga: his collaboration with Bay Area garage rockers The Chocolate Watchband.

No Way Out: Cobb and The Chocolate Watchband

The history of the Watchband is an agonizingly convoluted one, and beyond the scope of this (and nearly any other) article. But while any number of American garage bands channeled the stomp and pout of British acts like the Who, Stones, and Kinks—bands who themselves were, of course, merely attempting to channel American R & B—the Chocolate Watchband went further (think the Pretty Things or Yardbirds) and added a compellingly eerie, trippy side. Along with the Music Machine, another under-appreciated California band, the Watchband represented the very pinnacle of American proto-punk in the late ‘60s.

But unlike the Music Machine, who were largely (in the words of its leader Sean Bonniwell) “straight as ice cubes,” the Watchband had no compunctions about indulging in various chemical and plant-based divertisements. This would prove troublesome in the studio, where it appears Cobb took creative liberties. Some members of the band feel that Cobb’s production (especially on the band’s second album, The Inner Mystique) misrepresented them. They may have a point, seeing that some of the album’s tracks, a quarter of which are credited to Cobb, feature no actual band members.

Regardless, the album (and its predecessor, No Way Out) are now regarded as high-water marks of American garage rock. If Ed Cobb’s musical career represented an evolution from the “safe” vocal pop of the Four Preps to the “edgy” sounds of the Standells, his association with the Watchband was the most exploratory, and for those interested in the history of American underground rock, arguably the most enduring.

Cobb’s Coda

As the ‘60s ended, Cobb drifted out of music production and became, of all things, a champion horse breeder. He died of leukemia in 1999, aged 61. Over the course of his long career he’d earned a whopping 32 gold and platinum records and 3 Grammy nominations.

But for fans of underground music, it’s the non-hits that may stand the test of time. Songs such as “Good Guys” challenged the conformist bent of popular rock, if only for an instant. But for those few lucky enough to catch on, they were both a beacon and an inspiration to go against the flow.

Thank you, Ed…wherever you are.

Ed Cobb rules. He also wrote and produced Toni Basil’s first single “Breakaway.” he’s important.

Huge Ed Cobb fan. Despite being from Boston & well before the Red Sox adopted “Dirty Water” it’s the song of his I loved to hate. Well before Minor Threat released it & perhaps before they started playing it Boston’s The Outlets covered “Good Guys” live starting back in 1980. That’s were I heard it first and as usual tracked it down to it’s source. As I kept digging into the Nuggets & slightly off-kilter early ‘60s soul, Ed Cobb’s name kept popping up with regularity & with songs of unusual quality my teenage self could identify with. Thanks, Seth, for a solid overview.