Luck, Intuition, and the Violence of Self-Help

I can’t prove it, but I believe everyone who’s survived traumatic environments relied on two things: Dumb luck, and leaning into their native intuition. Right now is when we need them most.

Are we all having the same experience?

A friend said something the other day that stuck with me. He’s a big thinker—dreaming up whole neighborhoods that co-exist in harmony with their surroundings—and right now he’s stretching himself in ways that would’ve been impossible just a couple of years ago. “It’s not just that I’m learning new skills,” he told me. “It’s like I’m learning a whole new way of being. I know it’s what I asked for, but it’s really hard.”

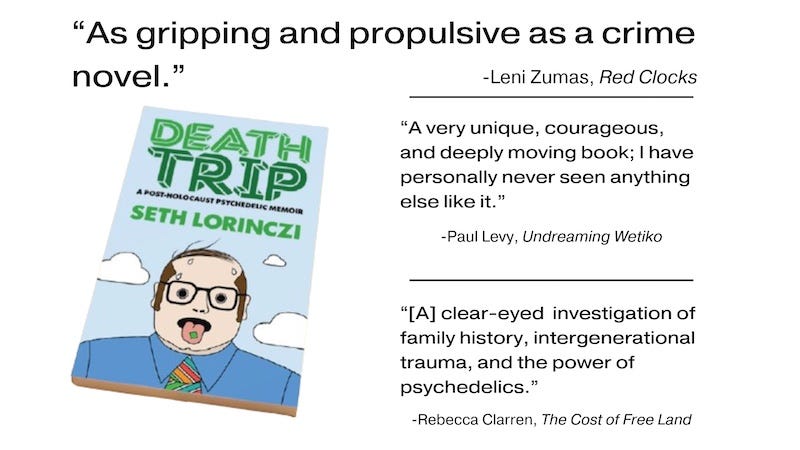

I know a little bit of how he feels. I’m in new territory, on the verge of publishing my first book and figuring out how to best share it. While my friend and I are on very different paths, we’re having the same experience, and it reminds me of something I stumbled on when I was researching my book: How the survival stories of those who lived through unsettling or traumatic times—in my family’s case, the Holocaust and the Battle of Budapest—are all eerily similar. They all center on a combination of dumb luck and a tuning into the same native intuition that artists and other creatives rely on all the time.

Let’s start with the luck piece, because that’s simpler. My father didn’t talk much about his experience of war, so the few stories he shared had a special charge. One of them hinged on a moment of dumb luck he experienced during the Battle of Budapest, in early 1945:

“We were hiding in a villa in the Buda Hills,” he said. “At night we’d stay in the basement, because it was safer during the air raids. Your grandmother was the appointed cook, because she could make anything taste good. One evening during a bombing raid I was sitting with my back against a concrete post, eating a bowl of macaroni, when I realized it needed more salt. This was strange, because my mother was such a good cook and she always seasoned everything perfectly. But this one time my noodles needed more salt, so I got up to go fetch some. Just as I did, a bomb detonated right outside the house. A piece of shrapnel burst through the awning window and embedded itself in the concrete post right where I’d been sitting. It wouldn’t gone straight through my heart.”

I was no older than eight or nine then, still young enough to play “Army.” I still remember the glow of specialness the story seemed to confer on my father—maybe even on me. I had no way of knowing it, but what I’d eventually learn was that everyone who survived the battle had more or less the same experience, with only details changed. A bomb fell on a different building; the checkpoint was to the right but you went to the left. In eerie consonance with my father’s story, the Hungarian author György Konrád wrote about an incident during the battle in which he was kneeling by the fireplace in an abandoned apartment, heating up a saucepan of soup. As he rose from the fire, he was surprised by a sudden hissing sound coming from the coals. A bullet from a Soviet ground-attack plane had pierced the windowpane and then the pot of soup, passing right through the spot where he’d been sitting the moment before.

That’s the luck piece. But there’s something else, harder to quantify but just as necessary. Everyone who survived tuned into their native intuition. They let go the illusion of control, taking the next right step without quite knowing how—and certainly without knowing where it would lead. They did what all artists do.

Believe me, that’s in no way meant to minimize the life-and-death risks survivors of actual traumatic situations undertook. In my father’s case, his turn towards intuition led him to the least logical (and most terrifying) leap of faith I could imagine: He hid in plain sight, defying both the authorities and the odds, and it worked. He lived, and in the process…well, I’ll save that particular story for the book.

Here’s what I’m getting at: We can’t control dumb luck, apart from doing fewer dumb things—like climbing 100-foot tall construction cranes while you’re 16 and high. (Not that I did that, ever.) But intuition can be honed, and we can change how we relate to it.

My daily experience doesn’t involve life-or-death decisions, besides the normal ones associated with driving a motor vehicle, or choosing the wrong coffee mug. But for many hyper-sensitives, simply waking up each day can feel like a life-and-death decision. Reading the social, political, and environmental winds, it’s safe to say that anxiety will only increase in the coming years, but intuition is its antidote. I don’t know about you, but whatever I can to tune out distraction and increase my access to intuition—reducing screen time, sitting in silent meditation, being physically active and engaging with my community—no longer feel optional, but mandatory.

It’s ironic that there’s never been a better time in history to share our creative selves—so many tools and platforms, such a burning hunger for greater consciousness—and yet so many of us feel irrelevant, cut off, subsumed in the thrashing surf of social media and all the other hindrances to true connection. I credit much of the fact that I don’t experience the extreme levels of anxiety many others do to sharing my own art and partaking of others’ (I’m going to provide a short list of current reads below).

Part of the problem is the sheer glut of “advice.” According to the internet, roughly 15,000 self-help books are published each year (that’s about 41 per day). I’ve read a few myself, and some have helped illuminate hidden aspects of my habits and character. But many just feel punishing, hammering away at the message that we’re just doing it wrong, that there’s always another plateau to reach, that if we only make the last 5% of effort (or shed last those last stubborn 5 pounds) we’ll finally be free.

Which returns me to my current predicament. Like the friend I referenced earlier—the one who’s daring to shed the safety of his old identity by stepping into big dreams—I feel a welcome wind at my back, even as the technicalities of publishing and sharing a book can make me feel like I’m pitching a tent in a sandstorm.

When I think about the stories that thrill me—the ones that make me feel like I’m not alone, abandoned, or forced to figure it all out by myself—I recognize that they’re all about the act of reconnection, regrounding, and rehoming. They’re about remembering that we already have the tools we need; we just need to close our eyes and find them.

So, a short list of some of the things I read the past week that excited me:

Alex Dobrenko` writes movingly (and hilariously) about struggling with addiction, among many other topics

Kerala Taylor writes about being a mom and finding meaning when the lights go dim

And Don Boivin navigates the world as a man who’s learned the hard way that he needs tenderness, too

Do you have a routine, a prayer, or an incantation you use to reconnect with your native intuition? Share it in a comment. I guarantee there’s someone reading this right now who could use it.

Hey, Seth, thanks for mentioning my work. I’m really glad you liked it; that’s a compliment of the highest order! I exercised self-control and read your essay without first scrolling down to see where you mentioned me ha ha. And I enjoyed every word. That’s a good bit of writing!

Um, reading Substacks like this.

Also quitting my full time job so I can get in touch with my creativity (which is a privilege) and access parts of my brain 🧠 that were demanding more spiritual and physical attention