The Lone Wolves: A Crisis of Manhood at the Oregon Coast

What drives young men to plot assassinations? Start by looking at the men raising them, and a culture that derides emotional connection—oh, and Jesus Christ—as “weak.”

For several months now, the words “Lone Wolf” have been staring back at me from the notepad where I jot down ideas for these posts. The words were there long before 20-year-old Thomas Matthew Crooks loosed a volley of rifle shots at former President Trump, and before Summer Koester published one of her typically haunting and insightful essays with that phrase in the title.

Not that it’s a particularly noteworthy phrase, except perhaps to the actual lone wolves killed in Oregon last year (33), fully half by vehicular collision, poisoning, or illegal hunting. Nor have wolves, lone or not, historically been something I really had to think about. But a few years ago, when my wife and I went in on a tract of land on the Oregon coast with another family, I started meeting some lone wolves in person. The human kind, that is.

The coast is an interesting place to find myself. In case we haven’t actually met, I present as the kind of person once labeled “metrosexual.” I’m not rugged, strapping, or inclined to wear work boots or baseball caps. My voice is sometimes described as “effete.” I typically feel slightly uncomfortable in farm stores, tractor implement suppliers, or gas stations.

Oh, and did I mention I’m Jewish?

But here’s the thing: I like connecting with people who aren’t like me. Scratch that: I downright love it, and a few chance encounters with strangers rank among the most memorable experiences of my life. But a brief (and very unscientific) sampling of interactions with men out here stick with me, and not in the peak experience way. Call it coincidence, call it something in the collective field, but I can’t let go of the sense that of all the members of our society, it’s most of all men who’ve lost their way.

Man One: The Defeated Neighbor

Sid lived in a hovel next to me at the end of a quiet valley. Hovel: That’s a word you don’t get to use much these days, but there’s really no other term for Sid’s former dwelling. It was a ‘70s-vintage single-wide that had only a few years prior been in good trim and reasonably protected against the depredations of the temperate rain forest that prevails here.

These days, the structure is uninhabitable by any standard definition, having literally soaked in refuse for years. Inside it is truly horrifying. I’ve got a strong stomach and have done some nasty chores in my life, but I can barely even stand to be near it.

Sid is probably 54 or 55 now, but seems far older. That’s in part due to some physical challenges—he smokes constantly in spite of having suffered five heart attacks in the last four years, and he carries at least an extra 125 pounds on his already hulking frame. But it’s his conversational style, for lack of a better term, I’m referring to here.

Sid speaks at, not to, anyone who will listen, spilling out long lists of hardships and disappointments. There’s no conversation per se, and he never asks questions. It’s more an endless cataloging of failures, disappointments, and fuckery perpetrated by others.

I like and care about Sid, but these monologues are hard to endure. I can’t help but feel like I could be anyone, or no one: Just a person-shaped receiver for his grievances.

Sid’s not a father, though for many years he helped raise a boy he didn’t father. From what I can tell the child—now a young adult—is struggling, as are so many young men his age. And while Sid doesn’t say it outright, he and the boy don’t have much contact.

Sid is, in my judgement, a deeply intelligent, sensitive, and articulate person, but he has no access to the basic emotional language that is the key to connection. He seems totally walled off inside himself, pacing the ramparts of disappointment even as they—like his former home—literally disintegrate all around him.

Man Two: The Talker at the Trailhead

Last year, I encountered a man at the trailhead where I often pause on the way to and from Portland. Similar age and build as Sid, similar aesthetic—let’s call it “Backwoods Man Bear.” He was friendly, and I was pleased to engage with a stranger, if only for a moment. “I’ve been coming to this spot to camp for years,” he told me, pointing to his kitted-out pickup truck parked nearby. “Used to be a lot different.”

I pressed him for details—I love the small, unwritten histories of places you only encounter at the face-to-face level—but I soon realized, with dismay, that this wasn’t what I was going to get. With little preamble or invitation, the man launched into a roll call of letdowns and gripes: The family members who were ignoring him (can’t imagine why) or the various failures of local governmental agencies and representatives. I tried to turn the conversation back to something historical, or more probing, or anything at all resembling a conversation, with no success. After a few minutes I left, as politely as I could.

The guy didn’t seem disordered or of unsound mind. It wasn’t that he was disrespecting my time and attention (he was but trust me: they’re cheap). But I left feeling unsettled, as though I’d just interacted with a very convincing likeness of a person. Like Sid, the man seemed emblematic of a very specific self-absorption, one that demands emotional caretaking while offloading the actual cost of this labor to spouses and partners. And after those partners leave, to strangers they encounter at trailheads, before those strangers get tired of being talked at and themselves leave as well.

Man Three: Young and Angry

Finally there was Tim. I was trying to troubleshoot a log splitter. (Yes! Incredibly, I can operate a log splitter, with a reasonable degree of safety.) Having no luck, I’d gotten his number from a former logger I’m friendly with.

I was excited to meet another neighbor of mine. But when Tim arrived, I was struck by the halo of literal and figurative darkness around him: Dark hair, brooding eyes that wouldn’t meet mine, a dark t-shirt emblazoned with a facsimile of the Declaration of Independence on the front and “Let’s Go Brandon!” on the back.

In the ten minutes or so Tim and I interacted, I turned over a few conversation-starters in my mind, dropping them all one by one. He didn’t want to discuss the log splitter other than in monosyllables. He didn’t want to talk about how he came by his impressive mechanical aptitude. I could see no way into conversation, no way towards an even topical point of connection. It wasn’t menace he projected; more a deep insecurity that had hardened into icy silence. He left as soon as he could.

So…What to Do?

That last interaction was nearly a year ago, and yet I’m still thinking about all of the men I meet—not just at the coast, but all over the country. I can’t help but feel that the darkness enveloping Tim—or the one that enveloped the enigmatic Thomas Matthew Crooks, the young man who last week expended his life in an act of pointless political violence—is inextricably linked with the emotional paucity of men like Sid and the man at the trailhead.

Little is known of Crooks, a lonely and aloof outcast who dressed in camo and hid his face behind an N95 long after public health warnings were dropped. But really: What more do we need to know other than that he—like countless other men standing at the cusp of adulthood—surveyed the men who’d raised his generation and decided, not unreasonably, that nihilism was the only viable choice?

These young adults are looking at their elders and seeing a generation of men who lack the basic architecture to connect with the outside world—even, in some cases, to care for themselves on a physical level. Who looks forward to that? Small wonder that images of forcefulness and power are so prevalent, or—as Summer points out in her essay—that so many so-called Christians feel that Jesus’ teachings are too “weak.”

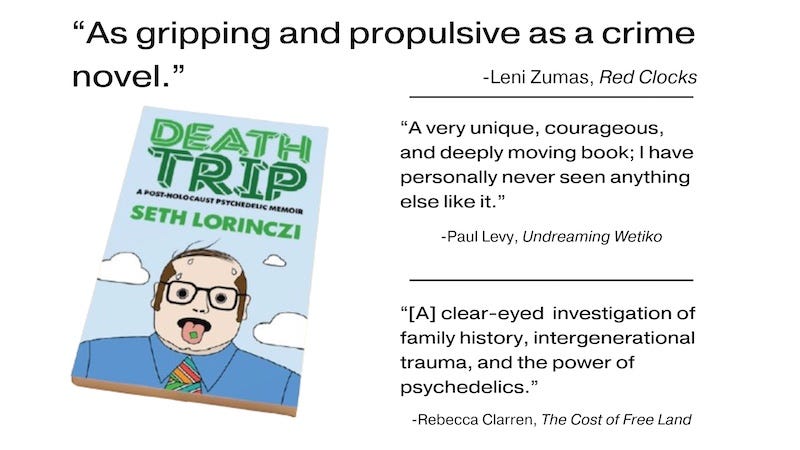

The power that comes from rejecting “unmanly” emotions is a dangerous one, an electric current of rage that must find ground. It reminds me of something I stumbled upon in researching Death Trip: In the '70s, the sociologist Klaus Theweleit suggested that the men of the Freikorps—a German paramilitary force formed in the wake of the First World War—were motivated more than anything by a fear and distaste of women and their growing participation in society. Many would go on to form the nexus of the future Nazi Party, including SS chief Heinrich Himmler, his rival Ernst Röhm—the head of the Storm Troopers and a closeted homosexual—and Rudolf Höss, who would eventually become commandant of Auschwitz. Many modern-day far-right groups, I’m told, use grievance against women as their lure, with impressive results.

Yikes.

I feel nervous around many of the men I meet at the coast. I imagine—with some cause—that they don’t like that I live in Portland, or that I’m not manly, or that I have no interest in shooting wolves. (Did I mention I’m Jewish?)

Still, I want to find common ground with these men. Connecting with people is something I know how to do. It makes me feel less hopeless, and I believe it does the same for others. The essential experience of this historical moment is the feeling of powerlessness. Maybe, just maybe, this is its antidote.

Seth - thanks for articulating this, brother. Lust for power is greatest in those who feel they have none at all.

One thing that comes up for me is my lifelong task of reconciling these worlds. It's a question of home.

I am of that ilk, originally trained to zip shut or blame others for my lot, to isolate with my clanking band of machinery and pain.

In healing so much of that material, I am a ghost to my former folk: at the Oregon coast, in Alaska, even as a carpenter, though I speak the language and know the postures, the ways in which my suffering shows up now is just a little too .. different to feel like I belong.

Living in Alaska, so many men I know I recognized in your piece. Beautiful read, as well!