The Trauma Brothers

From the war in Gaza to the Black reparations movement and beyond, ancestral trauma is having a moment. Could a film about a little-known doctor be a missing link?

Something is in the air. At my book launch a few days ago, a friend mentioned that he’d been “saved by Sarno”—he used that exact phrase. Later, a podcaster who happened to be on an email thread in which I referenced the film Saved by Sarno asked if I was referring to John Sarno, who’d cured his chronic back pain as well. Last night, at a reading in a small beach town in Oregon, a woman yelped “Yes!” when I mentioned Sarno during my book talk. “I’ve been thinking about him the whole time you’ve been speaking!” she said.

My book, I should point out, has absolutely nothing to do with John Sarno.

It was clear a lot of people needed healing, and whatever this Dr. Sarno was doing, it seemed to be helping.

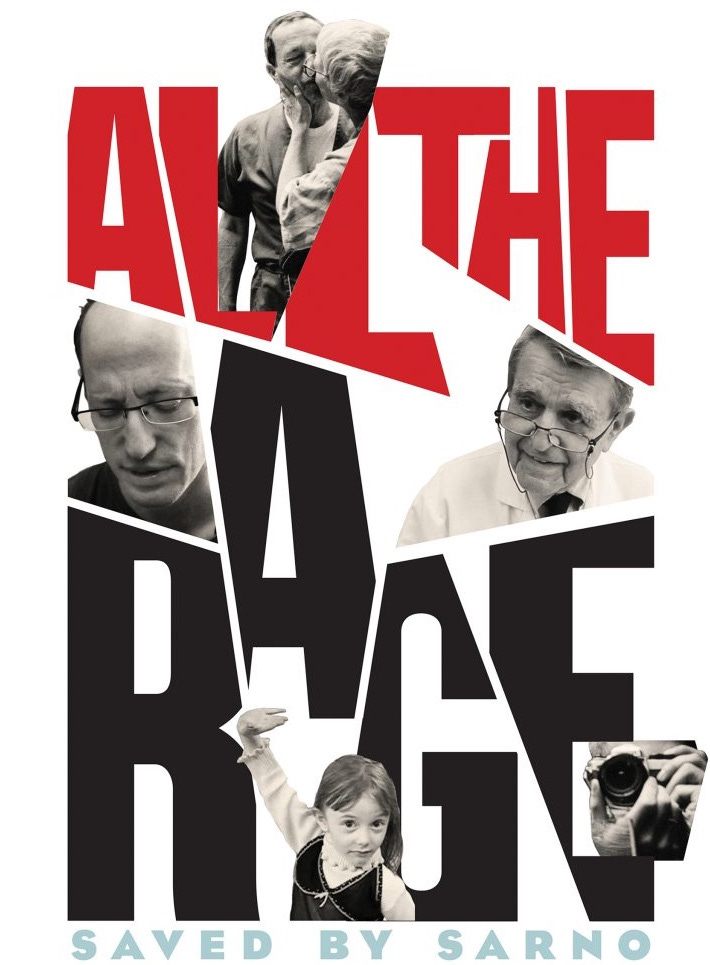

I’m not a film guy, so it was odd that I knew the documentary (the full title is Saved by Sarno: All the Rage). But I’d actually seen it—not once but twice—and it had affected me deeply. In each and every frame—and it’s an aesthetically beautiful movie—I felt like the filmmaker, Michael Galinsky, was somehow expressing my thoughts out loud. And many of them touched on the topic of ancestral or intergenerational trauma.

I recently published a book on ancestral trauma myself—it’s called Death Trip: A Post-Holocaust Psychedelic Memoir. It’s a story about my coming to grips with the epigenetic coding I was handed at birth by the Holocaust Survivors who raised me. In a nutshell, the takeaway is that when trauma remains unacknowledged and unexpressed, it directs our actions in unanticipated (and often destructive) ways.

All the Rage approaches the topic from very different vectors. It’s a documentary about repressed emotion, chronic pain, and social injustice, whereas my book is a personal narrative about a quest for buried family secrets. But both works point at much the same thing. That when emotions—typically rage—are ignored, they make us sick. Very, very sick. And from the war in Gaza to the rage empowering the BLM, Black reparations, and Occupy movements, ancestral trauma is the common thread.

Chronic Pain, Emotional Disconnection, and Intergenerational Trauma

Michael Galinsky and I have never met—so far as either of us can tell. But a few months ago, I began to notice that whenever I’d read his posts and see his quietly astonishing photographs, I felt as though he was saying my thoughts out loud. Whether about family, ancestry, or the deeper meaning of the underground scene we’d both been a part of, he was shining an uncomfortably bright spotlight on the ways our suppressed emotions—even those of our forebears—dictate our actions and rule our lives today. And for each of us, finding the others’ work feels like a puzzle piece snapping satisfyingly into place.

Galinsky and I should’ve known each other, judging from the Venn diagram of the punk and indie circles we moved in during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Some scenes from the 1994 film Half-Cocked, which he made with his creative partner and now-wife Suki Hawley, involved people who lived at The Embassy, the Washington, D.C. punk group house where I’d once lived. But it was only when I watched Saved by Sarno: All the Rage that it all came into focus. Galinsky and I were trying to answer the same question, only in different ways.

All the Rage is, on the face of it, a film about a pioneering but largely ignored physician, Dr. John Sarno. In an era when medicine was turning towards surgical and pharmaceutical interventions as a response to the rise of chronic pain, Sarno focused on repressed emotions as the source. When Dr. Sarno advised his patients to make the connection between their emotions—including their tendencies to put themselves under extreme pressure and stress in order to appear “perfect”—to their physical symptoms, they rapidly improved. And one of his critical understandings was that the tendency towards perfectionism and the tendency to care for others at the expense of the self was related to childhood trauma.

My book began as a bid to revisit my life story. In middle age, a cascading series of crises—the looming dissolution of my marriage and the end of my bid to be a professional musician—forced a long-delayed reckoning with my backstory and the painful emotions I’d never allowed myself to feel.

A moment ago, I wrote that Galinsky’s film is about Dr. Sarno, but Galinsky himself ends up being a central character. Similarly, I began my book believing it was the story of my ancestors. The project was already well underway before I realized that I had to play the central role. What’s less stated—but equally true—is that both works are attempts to reach our fathers, both of whom are now dead.

I decided it was time for Galinsky and I to talk. What follows are excerpts from a still-unfolding conversation about the interlocking themes of our work.

The N of Two: Parallel Paths Towards Understanding Intergenerational Trauma

S: Earlier in this conversation you said “N of one.” What does that mean?

M: That’s a term from clinical studies. The “N of one” means a single patient being given multiple randomized and blinded treatments. So I think we’re the N of two.

S: I love that! I wrote a memoir; you made a doc. And as I said previously, it’s eerie it’s like we’re both asking the same questions. And there’s also a parallel in structure. At first, I thought “Death Trip” was about my forebears and what they’d lived through. Eventually—and uncomfortably—I realized it was about me. How did that play out for you in the making of All the Rage?

M: I came to see that I had to be in the film in order to help people connect with their own emotions. One book I read in college was Joseph Campbell's The Power of Myth. In it he breaks down the basics of almost all religious stories, which tend to tell the tale of a hero overcoming some incredible odds, largely due to faith. Part of the reason this kind of storytelling is so relatable is that not only are we told these stories from childhood, but because they also help us to have hope that if we just believe, we might succeed. That we might be loved.

While Dr. Sarno's journey to get his message out was heroic and effective, he wasn’t willing to be the kind of character who might be emotionally naked in our film. That's what made it stall in the first place. We started the film in 2004 and by around 2006 it was clear that we were stuck. He wasn't doing anything in public, and he wouldn't introduce us to patients. In our first two years of trying to make the film we only filmed with him a handful of times. We were immersed in the idea of following a character, and since we had no way to do that there was no way to move forward.

Also, when we started to make the film, people weren't ready for it. Not only was there no way to raise money, there was also a lot of direct antipathy to the idea that emotions, or trauma, could cause physical pain.

When my own pain came back in 2011 I became painfully aware that I had to be in it and I had to be emotionally naked if it was going to work. The good news is that it absolutely helps people to connect to the emotional underpinning of this story: It's about how emotions affect us. If it can't get people to feel their own emotions it's not going to help them to understand the power of their own brains and emotions.

S: How did you find Dr. Sarno in the first place?

M: When I was in second grade, my dad almost died of an ulcer. It was very traumatic. After he recovered he got back pain from a very mild fender bender, and it lasted for years. Finally someone gave him Dr. Sarno's book The Mind Body Perspective which explained Dr. Sarno's insight: That most back and neck pain was caused by the brain in order to distract one from feelings that were more scary than the pain.

My dad was a psychologist who got it right away and largely healed. So he talked about the book all the time and shared it with people. A decade later my brother had hand pain so bad he almost had to drop out of graduate school. He was going to get surgery to carve away his collar bone, which was supposed to free a nerve. My dad told him he'd never speak to him again unless he went to see Dr. Sarno. So he did and he got better. My brother was skeptical because he didn't think Sarno had good science, but he got better quickly.

He got better in 1994. At that time, my back would go out once or twice a year for a day or so. When I read the book I completely understood the ideas and almost banished my pain for a decade. But when it came crashing back, in 2004, I finally ended up in his office. Before I was totally crippled by the pain I kept trying to read the book, but for some reason I didn’t even consider trying to go see him. Seeing him in his office—my wife had to carry me in—wasn’t miraculous but it got me turned in the direction of faith and belief and I started to heal. That’s when we reached out to him to ask if he would let us make a documentary.

S: What did this illuminate about your own family history?

M: Dr. Sarno's basic thesis was that due to trauma in childhood we carry hidden wounds into adulthood. When these wounds threaten to rise to the surface, the patterns that we learned to protect us from trauma-inducing behavior send us into reaction mode, flooding our bodies with stress hormones and prompting our brains to distract us with thought patterns.

The pain is real. However, chronic pain arises from a different part of the brain than acute pain, which helps clarify that the pain is from an emotional part rather than one that responds to actual physical threats rather than physical injuries. When we made the film, the phrase “trauma informed” was not yet in use. A lot has changed since then and it's kind of wild to see the shift.

One of Dr. Sarno's insights came from the fact that most of the back pain patients he saw were between 25 and 55. If back pain was supposed to be due to tissue wear and old age, why were so many of his worst patients only in their 30s? He postulated that the pain was connected to the overwhelming double burdens of parenthood and career expectations.

This made sense to me. My pain came roaring back when I was 34 with a kid, a house, and too much debt and responsibility. My father's illness came on when he was overwhelmed with parenting three young kids and working as a professor with a professor wife he frequently fought with. That all makes sense to me too. Sometimes it’s only looking backwards that we can see patterns with any clarity. When you are in the maze you can’t see it.

One thing that I try to work through in the film is the loss of my father, who was saved by Sarno forty years earlier. He grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust. Both of his parents fled persecutions (from Lithuania and Belarus) in 1908. My father was born in 1934; in 1942 the Nazis moved into Lithuania and encouraged the locals to kill their Jewish neighbors and take their property. Within a few months of the well-known Kaunas pogrom, almost every Jew in the country who hadn’t escaped had been killed.

Growing up I knew nothing about this; it explains a lot. My father embraced Jewish humor, writing, and films, but rejected everything having to do with religion. This is another reason I became a religious studies major. It was not to piss off my father, but instead born out of a curiosity about things I hadn’t been taught.

My father's death was very traumatic for me. Shortly after he retired he started to have all kinds of joint pain, weakness, and muscle wasting. He had gotten weaker—and I think more depressed—when he was hit by a car trying to cross a highway to go to a basketball game. My mother had dropped him at the light and gone to park a couple of hundred feet away. The car hit him and it continued 400 feet before pulling to the side. The driver thought he had hit a deer.

While my father and I struggled when I was in a band—because he was not supportive—we had gotten to a good place by the time he passed away. Still, I sometimes wonder if getting hit by a car was a total accident. One of the first things I read in college was Sartre, and I remember his contention that the reason people step away from a train coming into the station was not the fear that they might fall onto the track, but instead that they might be tempted to jump in front of it.

In any case, when he died I was thinking about his difficulty with retirement as related to issues with sense of self, but I wasn't thinking on a deeper level about his parent's childhood trauma might have affected him, and how that in turn affected me. In fact I wasn't really thinking about that on a deeper level until I read Death Trip.

I read quite a bit about these issues. Gabor Mate's book When the Body Says No made me much more aware of how trauma flows between generations. Death Trip made me much more aware of how my parents’ trauma affected all of us in ways that we didn't fully understand. In fact, I think that the way in which they had been unconsciously taught to put the past behind them—but also to be vigilant for threats—was because their parents had never dealt with their own trauma.

Even though both of my parents were in mental health fields (psychology and social work), they were completely unaccountable people. They fought all the time, and that in itself was traumatizing. When we pressed them on it they said it was better to model expressing one's feelings rather than repressing them. The problem was, they weren't actually dealing with their feelings. Instead they were reacting to their traumas, which felt like feelings, but were instead learned (and genetically transferred) patterns of behavior.

I can't remember the line in the book that sparked this awareness, but I was struck by the thought that my parents fights were different than I imagined. I always remembered my mom stage-whispering in my dad's ear about some way that he was transgressing. I often thought that she was being the problem—she was in many ways—but what I noticed now was a recognition that my mom was so angry because my father couldn’t listen or be accountable. Rather than turn to her and say "you're right, I'm sorry,” he would apologize but not mean it.

My point is, your story helped me to see not only a connection between our stories, but a deeper generational pattern of hiding one’s own traumas to avoid having to deal with them and in so doing kicking the can even farther away. How do connect with a trauma that we haven't really experienced firsthand?

In noticing just how unaccountable both of my parents were, and how much suffering that caused in their later years when they lost a lot of their thinking capacity, I've become even more committed to dealing with my own issues. All The Rage, our film about Dr. Sarno, was just a small step in that process.

S: I’m struck by the forward-thinkingness of the film, and how it’s perhaps more relevant and timely now than when it was made. What are your hopes for it today?

M: One of the doctors in the film quotes Thomas Khun, pointing out that in science thought leaders are at first ignored, then attacked as crazy, before they’re shunned. Then, when their ideas are adopted, people say: “We knew it all along.”

We experienced a bit of this ourselves. Our film came out a bit too early for people to understand its relevance and the way in which it wove together ideas related to trauma, medical, political, social, racial, gender, and economic connections four years before COVID and the racial reckoning. Since then, all of these systems are being challenged anew and ideas related to trauma have become much more widely accepted and discussed.

I think All The Rage ages well because it's not making arguments about data or facts, but instead pointing out something that we all know innately. The last line of All The Rage is Dr. Sarno stating: "It all comes down to one simple idea; that the mind and body are intimately related. That's it. That's the whole story.”

It is the whole story. We all know this, but often find it hard to believe how true it is. For that reason, I think Dr. Sarno will continue to get his word heard, and our film will continue to help make that happen.

Watch the Movie

As I wrote at the top, it’s eerie how many people are connecting the themes of Galinsky’s film and my book, a growing communal conversation bubbling just beneath the surface. If you’re interested at all in how repressed emotions and unexamined trauma are impacting us, I can’t urge you strongly enough to watch the film. You can stream Saved by Sarno: All the Rage on Vimeo, Amazon, and elsewhere.

Oh! And I suppose I should plug the book, too (I’m writing from beautiful Gold Beach, OR, where I’m stopping on my way to more book events in California. Catch me in the East Bay or Portland, or buy your copy here. It’s been a true pleasure getting notes—many from people I’ve never met—telling me “I see myself in your story.”

I’m so glad you wrote about this, Seth, because I had no idea that documentary existed. Reading Dr. Sarno’s books “Healing Back Pain” and “The Divided Mind” helped me immeasurably. I’ve recommended them to many people.

I'm working my way through The Body Keeps the Score now and this feels like a great film to follow it up with. Thank you for putting it on my horizons!