"They Hate Babies and Old People": The Story of 9353, Evil Clowns of the D.C. Punk Scene

Rock is full of “shoulda made it” stories, but this isn’t one of them. In the D.C. punk scene, 9353 were the bad guys. They were also eerily gripping and wildly popular. What went wrong? Everything.

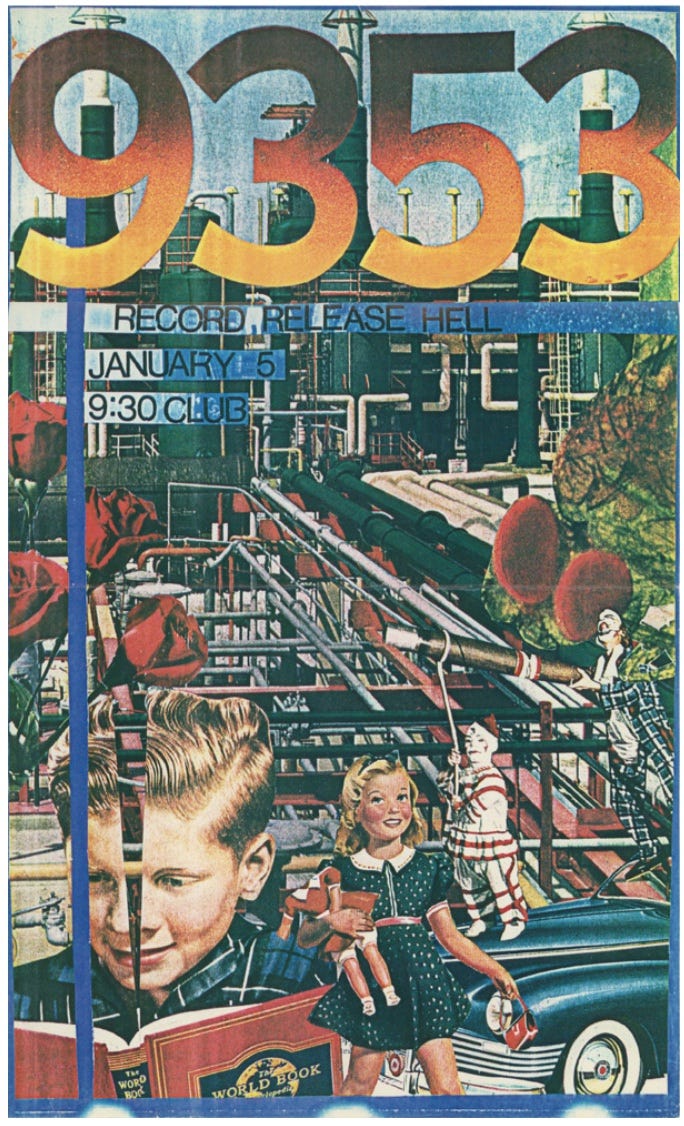

It was the posters that started it.

Long before I’d started going to punk shows—long before I knew such things existed in the buttoned-up Washington, D.C. of the ‘80s—I’d see them wheat-pasted to lamp posts and mailboxes. They were simple, graphic, and unsettling, with stark, cheerful images juxtaposed against menacing backgrounds. Providing minimal information save a series of ominous-seeming numerals, they hinted at an underworld behind the city’s bland facade. I wanted to know more.

I would learn more about them, though it’d take a few years. More an art project than a functional band, 9353 came on a bit like the early Devo—when the Ohio group led with their more scabrous tendencies. Playing a caustic, sinister, and darkly funny brand of punk light years away from straightedge hardcore, 9353 eschewed power chords, lightning-fast tempos, and shouted vocals. Instead, singer Bruce Hellington’s startling delivery suggested multiple personalities—sometimes within the same line. And if Devo pointed at society’s failings, Hellington had no compunctions about pointing directly at your own.

Between 1983 to 1986 the band garnered a large local following, sometimes playing two sets a night at the 9:30 Club on F Street and, for one record release, a one-week residency at nearby d.c. space. Then they vanished, leaving little legacy but two hard-to-find albums and those spectacular posters, fading under the pitiless Washington sun.

Why revisit them now? The story of 9353 is a glimpse into a bygone world: Of D.C.’s downtown arts scene, of once-grand department stores vacant and rotting, of rampant drug abuse, critical indifference, and suburban rage. It’s less a story of what could have been than a reminder of what can never again be.

There’s something else: 9353 existed in the final moments before the underground burst out into the open. Their power lay in their unknowability, in the shadowline of dark humor bleeding into fervid malice. Suburbanites in a largely urban scene, they were outsiders among outsiders—and thus perhaps damned to be forgotten. Their brief lifespan coincided with another liminal zone: the end of the pre-internet era, the final moments before the digital age gave us a way to preserve nearly everything—but perhaps lessened our ability to discern. So much has been gained, but I’m more concerned with what we’ve lost. And as malignant, self-defeating, and just downright weird as 9353 were, they deserve far more than to be merely forgotten.

A few words about this profile: Writing about a collaborative project such as a band is challenging under the best of circumstances. One member of 9353, Vance Bockis, died in 2012; another, Bruce Miles Hellington (aka Bruce Merkle), graciously declined to be interviewed. All quotes attributed to him are taken from an interview conducted by Damon Locks, and originally published in Stop Smiling magazine in 2009.

As perhaps the chief chronicler of the band, Damon is himself a voice in this article. A fixture of the Chicago arts and music scene for decades—as a member of Trenchmouth (not to be confused with the earlier Washington, D.C. band) and, more recently, performing both under his own name and as a member of Black Monument Ensemble—Locks grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where our story takes place.

Finally, this article is presented as though it’s a conversation—which is, admittedly, misleading. I spoke with Damon, Dan Joseph, and Jason Carmer; Damon spoke with Bruce Hellington. But for the purposes of continuity, I chose to interweave all these voices, offering context where—I hope—it serves.

Outcasts Among the Outcast

If the D.C. punk scene will forever be associated with straightedge and progressive activism, 9353—avowedly neither—was the exception who proved the rule. And like all underground music and culture in those days, one had to stumble upon them to even learn of their existence.

Damon Locks: I was a little Black kid from the suburbs. I grew up liking disco music, The Temptations, Earth, Wind & Fire, Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick. My mom liked Helen Reddy, West Side Story, Jesus Christ Superstar. Those are the things I grew up with.

[Then] older folks started making me tapes. And [I thought]: This is crazy music! But I lapped it up: Joy Division, Bow Wow Wow, Sex Pistols, The Clash, all that stuff. It was coming out of left field for me. And then even more so hardcore music: Fear, Iron Cross, all these things were coming at me. And hardcore didn't really make any sense to me until I saw the Silver Spring band Body Count, and that clicked.

So this was like entering another world. And yet inside this world was this other world that was 9353. And the fact that I love 9353 so much does not surprise me, because there's always been this person that was interested in the…the lack of safety in sound, the lack of safety in art. And 9353 was very unsafe.

Bruce Miles Hellington (9353 vocalist and lyricist): I spent most of my time from 1973 to 1980 hitchhiking around the country. I didn’t go to school for the most part. I learned everything I know about people way before I ever got involved in punk rock. I know that everything I think is not that original. In the end you become impressed with a lot of people no one notices and unimpressed with a lot of people everyone notices.

Jason Carmer (9353 guitarist): I met Bruce when I was about 15 years old, and we did a band called Color Anxiety. We played two shows. We played at the Corcoran art gallery, and then we played a barbecue. That was actually, I think, probably the best band that I was ever in. There was this guy, his name was Bobak Mogadan (sic), and he ended up in D.C. because he was Iranian, and his father was an advisor to the Shah. And he was just this really, really smart guy. He passed away, unfortunately, way too young, but he ended up going to MIT on a scholarship. So he was a trip, he was influenced by music from [that] background. And he had a lot of alt tunings, like really weird tunings, and he was kind of the driving force of that thing.

Bruce: It was a kinda new wave Roxy Music thing. We had a musical genius that was writing the songs for us. He ended up in our high school hanging out with us. It was Spring of ’81. That was where I honed my little bag of tricks or even learned to do them at all. I was pushed into being a singer in my friend’s bands because they said I looked like a singer and they didn’t have a singer. But I had a steady dedication to being a childhood alcoholic and a criminal. I had no musical anything other than being a consumer.

Seth: The third original member of 9353 was Vance Bockis, a Falls Church native. By the age of 16, he’d already played bass in Pentagram—a legendary, long-running local band now credited as forerunners of doom metal.

Jason: I met Vance like, a year or two [after Color Anxiety]. He actually lived kind of in my neighborhood, and he was legendary because he played bass in Pentagram. The comedy is that the band is like massively popular in an underground way. I mean, I see Mexican kids with Pentagram shirts.

And I was always in awe of him, and he was kind of nice to me. So, basically, at one point, I was like: “Hey, man, you know, we’re both into stuff like Throbbing Gristle or Psychic TV or Bauhaus or whatever”—there wasn't very many people really into it. “Well, I know this singer guy, he's pretty weird….” Then we got a drum machine. So that's basically how it started. I think in a sense, though, it kind of became Bruce's band.

Joe Lally (Fugazi): Vance just looked like a rock star. He’d been in Pentagram for a minute, then he sang in The Obsessed. They opened for Dead Boys, and Stiv was really taken by Vance. They actually followed them back to Vance’s place—maybe to score a Quaalude! Then, years later, when I saw Lords of the New Church, Stiv was dressed exactly like Vance had been: Cutoff denim vest, leather pants, bandanas tied everywhere. Vance was our Iggy [Pop].

Seth: Unfortunately, Vance—like Iggy—had a long and often disastrous relationship with intoxicants. An addict for some 27 years, he once said of his torturous path: “If life were fair, I would be dead or I would be in prison.” In the last six years before his death in 2012—of a blood clot following rotator cuff surgery—he had finally gotten sober, was married, and working on new music.

The Horrible Truth About 9353

One of 9353’s enduring legacies is the sheer mystery attached to them—one greatly amplified by Bruce Hellington’s eerie graphic sensibilities. But over and above that was their name, which didn’t seem to attach to anything concrete. Or…did it?

Jason: How we got the name? It was a medical specimen that Bruce stole from Walter Reed Medical Museum. And it was pretty bad. It was a baby cyclops with a penis on his forehead. God! But the number on the sticker was 9353 and so yeah, that's how we got our name. He used to actually leave it in his refrigerator, so that way he could tell when people were scrounging around in his fridge when they were over at his house. That was pretty hilarious.

Bruce: If you hang a painting on the wall people will come after you with torches and pitchforks if you don’t have an explanation for that painting. You hang the same painting on the wall and you give them some stupid story and they will say, “That man is a genius.” So I came up with a story. The story was true. The thing did exist. The number I did scrape off. That was not the number but I told the whole world it was because I am giving them an art story.

Damon: The stories in song were performed like a demented radio play with different voices to match the different characters.

Bruce: Alice Cooper and Nina Hagen are probably the two singers that showed me (by example) more of what to do or what could be done. I wasn’t really doing anything other than being completely willing to make a fool of myself. It was one night in March or April 1981 that I was knighted with a magical wand. I woke up one day and I had a voice that could meet my imagination. This was a major factor, I didn’t own any of this stuff (gestures to his effects pedals), every effect that I had heard other people doing, I had to learn to try to do without [the help of effects]. I just had to mimic it.

Seth: Meanwhile, Jason Carmer and Vance Bockis created a sometimes entrancing, sometimes dissonant architecture out of arpeggios and mechanistic bass lines.

Bruce: I would say, if I was to be completely honest, the three greatest contributors to what 9353 was to become musically came from…one was local, Jim Altman’s band Scandals. They were a glam-rock / art-rock band in the late ’70s that we were just in awe of…that was the band that first showed us that kids on your street can be as great as any rock stars you’ve grown up listening to.

The two [English] bands that really hit home for us harder than any American band were The Stranglers and Punishment Of Luxury. No American bands that we knew of received that information and knew what the next link in the chain should be. We felt burdened by that responsibility.

Jason: Yeah, we were really into The Stranglers. And I think that’s how Vance and I hit it off. So basically, in a lot of ways, it's kind of like a ham-fisted Stranglers filtered through Arlington, Virginia.

It was exciting to explore things that you didn't really know where you're going to end up. Vance and I had this thing where we would just stand in front of each other and play. And then we would make changes, but we would never call out where we're going. So there were just these weird intersections of like, whoa, okay! And then, you know, neither of us really were, like, masters of our instruments.

I would come over to Vance’s house after school, and we practiced down in the basement, in his freaking house. He had this cat, Tumbleweed. So we would play, “I'll Tumble 4 Ya” [by Culture Club] while Tumbleweed walked around the house.

Then there was Fran, his mom. She was really sweet, she was definitely a character. And I don't quite remember; she drank, or she was on anti-anxiety meds or something. But I think we were driving her crazy because of our playing. And so she came downstairs and she started screaming at us, and then she said “I can be as mean as ten witches!” And then she fell into the bass drum case. So that’s the source of that song title [“Ten Witches” from the Bouncing Babies compilation LP].

I also remember watching the [1984] Grammys with Vance and Bruce when Michael Jackson moonwalked. And I remember we were all just like, “Holy shit! That's amazing!” Then going downstairs and being like: “Let's play!” I do remember that influencing us to go downstairs and work.

Seth: The fourth member of the band was Dan Joseph, today a New York-based composer, curator, and writer.

Jason: Vance got tired of pushing the buttons of this little fucking drum machine with his boot, so I was like: “Well, I know this guy who goes to my high school.” Dan was into Simple Minds and new wave. He just had a great attitude. He was kind of indifferent, so [I thought] he could probably hang with these guys. The cool thing about Dan is he played like a drum machine. It's great, because that's what we wanted, we didn't want a fucking drummer to be all hot dog.

Dan Joseph (9353 drummer): I was 16 when I first started playing [with 9353]. Jason invited me to participate in a demo recording session at [Don Zientara’s] original Inner Ear in Arlington. And so I was just brought in to add some percussive accents to the drum machine tracks. I mean, I never even really rehearsed with them. I don't think we even set up a full kit for this particular session, which was just four songs. It turned out, some months later, that I was actually in the band.

Evil Vibe-Masters of D.C.

In this era, punk was a home for truly marginal people, people who had no other way to interface with society in creative ways. And one senses that for the people in 9353, the only thing they could do is make this art.

Bruce: One of the things I have been able to do is reach into a lot of psyches and say, “I am on the exact same page as you.” Sometimes this backfires because a lot of insane people think they know me. I am basically really dedicated to attacking the inner psyche of the lonely alienated youth because that is what I was.

Seth: 9353’s humor was alternatingly absurd and malicious—both in song and in act. Allegedly, when Dan Joseph left to attend college for a semester, the rest of the band placed a death notice in a local paper, causing considerable upset among Dan’s friends. And the band’s—shall we say—oppositional stance to prevailing norms firmly established them as outsiders in an outsider scene.

Bruce: I gotta hand it to the whole Dischord crew, they were in the midst of instigating a huge international youth bully culture. We felt like we were the Beatles in the midst of all of this Rockers shit. We were focused on the kind of music that would just make a bully or a skinhead not want to sit and watch or hear us. The design of 9353 was to be purposely brash and antagonistic but in a manner that did not make skinheads feel good at all.

Jason: We liked David Lynch movies, we were super-obsessed with “Eraserhead.” William Burroughs was just like a God, you know? [We read] J.G. Ballard books, there was just this influence that was kind of left of center.

Damon: Not only were you introduced to the music, but then you started seeing midnight movies. So you're trying to figure out what “Eraserhead” is doing and what “A Clockwork Orange” is doing at the same time as you're trying to figure out this music. So it was kind of opening the door to this whole other kind of universe of thought. And 9353 was definitely the David Lynch of the D.C. scene, on the far edge of that.

Showtime

By early 1983, 9353 had a fully-formed identity; now it was time to take it to the stage. Damon Locks saw an early performance and was hooked.

Damon: It was 1983 at the 9:30 club, sometime around February or March. That was, like, the third month I was seeing shows. So they appeared almost immediately and they filled a space I’d never come across. Me and my group of friends from Silver Spring would go see them every chance we got. I used to describe them as: “They hate babies and old people.”

Jason: When we first started playing shows, people were like: What the fuck is this? Because we just had a drum machine, and we would do flood lights pointed out at the crowd, right? And just instantly, like probably three shows in, we had a couple hundred weirdos. It's just like: Where the fuck did these people come from? And these people would, like, wrap their face with tape and just dance around and crawl on the floor. Like: This is great! And I'm in high school, and there’s, like, pretty death rock girls checking me out, you know? That was when we were just truly weird.

Damon: I felt like the audience was just playing catch up. Like never did I experience the audience overtaking the group. 9353 for me, was always ahead of the game. I remember they opened up for PiL, an incredible show. That made perfect sense.

I’m 14, turning 15. I’d seen Minor Threat and Government Issue and Eric L's band, Double-O. But 9353 was doing something different. Bruce seemed to weave around, like his feet were glued to the ground but the top of him could move. And Jason always had a cigarette hanging out and seemed almost disinterested in the audience. Vance was very gothy, but also an amazing juxtaposition to Bruce in terms of a band dynamic. They were just strong characters that were very different. And Dan seemed like: How did the normal guy get in the band?

Seth: Years before I’d actually heard their music, 9353’s visual lexicon had already drawn me in. I could be mistaken, but my memory is that some posters didn’t even advertise specific shows, more announced the band’s presence.

Damon: It was definitely like going to a different land. You know, when you were at a 9353 show those flyers really kind of set the stage, and loomed even when you were watching the band.

Bruce: The thing is, I had nothing going on in my life. I was a homeless, drunk troublemaker who had a penchant for defacing property. Then all of a sudden it wasn’t painting…it was pasting! It didn’t qualify as the same kind of crime. It was very accepted.

Visually, I was influenced by the second Killing Joke record cover, What’s This For? It was so simple and very effective. That had a big influence on me. There was a singer in D.C. that I had admired for a long time because he had done a painting for every show they did. The Razz was the name of the band. But he never had them printed or put up in public anywhere. I was inspired by that idea.

A Certain Tension

In 1984, 9353 released To Whom It May Consume on R&B Records, a tiny local imprint. Though a promotional clip was made for the lead-off track, “Famous Last Words”—the video, depicting a fictional workplace shooting, hasn’t aged well—the album remained hard to find outside Washington, D.C. At the same time, the marriage of strong personalities and attendant issues was generating friction.

Dan: I mean yeah, sure, there was a lot of drug use in 9353 overall. But certainly, at least two of the members, half of the band, were regular heroin users and I guess arguably that's probably the cause for the [band’s] demise. I remember when we arrived in New York—this would have been in the late afternoon, so there was some time to hang around. I remember pulling up on Bowery where CBGB was, and we had a roadie who was also a user. So as soon as the van literally stopped moving and was about to park the users immediately disappeared, just hopped out of the van and whoosh, gone…you know, just out to score.

Jason: It was definitely, you know, some serious personalities in the band. [The music] was trying to do new things where you didn't really know where [it’s] going, like: That's really fucked up but it's catchy, yeah? So it was really about exploring, like, basically being weird.

Dan: From the very beginning there was a lot of tension with me being in the band, particularly coming from Vance. At one or even possibly two junctures, he literally quit for a matter of maybe six months or so, during which time we found a replacement bassist. But yeah, Vance wanted me out, and he gave them an ultimatum, like: Kick this guy out. Either he goes or I go.

It was ultimately rooted in antisemitism. He didn't want to be in a band with a Jew, and his mother sure as shit didn't want a Jew in her house, rehearsing in her basement. And she made that very well known during the fairly brief period, early in the band, when the band rehearsed in Vance’s home. So that was part of the band throughout, although I was so young, I didn't really…I didn't put it all together at that time. It was later that I came to understand what actually happened.

Beyond that, Jason and I got along well, we even did some side projects together. I mean, we were friendly all through that period and continue to be, actually. And for most of the time I was in 9353, I would describe Bruce as a mentor, and he was very encouraging. He was always super positive about my drumming and how well I get along with people, and how easy I am to work with and how I just should keep doing it.

Do You Hit the Road…Or Does the Road Hit You?

In 1984, 9353 embarked on a tour—or attempted to. Ironically, given their antagonism towards normative punk in general (and Dischord Records in specific), they purchased the former Minor Threat van. Paying Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson a $250 deposit, they hit the road to play a handful of dates set up by the now-defunct band’s guitarist, Lyle Preslar, then making a foray into booking. Fatefully, according to Ian MacKaye, the members of 9353 neglected to check the van’s oil before the start of the tour. Jason Carmer was already familiar with the vehicle, as it’d belonged to his friends in Scream before Minor Threat purchased it.

Jason: Yeah, pretty funny about that van: Before a Minor Threat tour, Pete Stahl (Scream) and I went and bought Limburger cheese, and then we put it on the engine block. They were actually really pissed, because apparently the whole tour, the van just smelled like complete ass.

Seth: But as it turned out, Minor Threat would have the last laugh.

Dan: The van broke down outside Pittsburgh or something. We did City Gardens in New Jersey and CBGBs in New York, and then we were on our way to Buffalo. But it was still a couple days off, and we stopped in a town in upstate New York that Jason had relatives in, called Lyons.

It was at that point that the cracks started to form. From what I remember, some of our upcoming dates did not appear to be as solid as we had expected. So we were in a little bit of disarray, and in the middle of upstate New York, and starting to discover our tour was a bit of a ruse. We also were invited on rather short notice to do a date in D.C. that Seth Hurwitz and IMP were presenting on Halloween, and that was a PiL concert we were invited to open for.

So we were on our way back to do that gig when the van literally broke down on the road somewhere in Pennsylvania at night—yep, oh my God—and somehow we got rescued by somebody, and that was the end of the tour, pretty much.

Jason: That was, I suppose, our high water mark. I mean, [in D.C.] we could draw like, 600, 700 people. We would go to New York, and I remember playing NYU and there being like, fucking 500 people or something. I'm like: What the fuck, they're all singing our songs? We got to a point where it was starting to kind of click up.

Bruce: It dawned on me about 10 years ago how fortunate we were to have failed and to not have to have gone out and suffered endless tours and successful things. We went out for two weeks once. We got ripped off at the only two shows that didn’t get cancelled. We waited for the third show. Then the headlining band, which was The Bangles, saw our record and kicked us off the bill. That was it! That was our big tour.

This Is The End

In 1985, 9353 released a second album, We Are Absolutely Sure There Is No God, which attracted the attention of the up-and-coming SPIN Magazine. But the review was largely dismissive, comparing the music unfavorably to Frank Zappa and suggesting that Bruce Hellington’s highly characteristic vocals were instead created by studio effects.

Jason: The second album, which was distributed by Dutch East India, actually got reviewed. [But] it was very difficult to imagine anything happening. I mean, both of those records were successful in the sense they actually did well in college radio. When I came out to San Francisco, all these people were like: Oh, you're in 9353? (Singing “It’s okay, it’s not loaded, I’m a good driver…” from “Famous Last Words.”) [But] we never could get our shit together enough to—or, I don't know, even cared enough to—try to take this to the next level.

Dan: We had released our second record, and we had played some big performances following that. We had some record label interest. [But] we didn't get picked up by Geffen and I guess we just sort of ran out of gas. It just sort of collapsed out of, I don't know, disappointment. We even had some new material that we were developing, some pretty good songs. But for some reason, we just all just, somehow simultaneously, decided to quit. That's the best I can explain.

Jason: I mean, back in those days, nobody got signed, you know what I mean? Like, nobody made any money. And it's like, the idea of just kind of driving around in vans forever…I don't think anyone was that into it, except Black Flag.

The other thing is that we had other things going on. Vance was really into his band Factory because…Vance was a singer. So I think he was totally into playing in 9353 but the truth is that he enjoyed singing more. It wasn't, like, all-encompassing.

You didn't really expect to be doing an interview in 2025 about it, you know? A lot of times those things, they kind of took on legs afterwards. I guess the point is: It was fun in those days, but after our shows, everyone would just get really fucking high and drunk and the whole fucking club would be just kind of like a madhouse. And eventually, you’re kind of like…how long we can go on?

Seth: What does the world need to know about 9353?

Jason: I kind of just like being obscure. It's like: Oh, well, you missed out. You know what I mean? There's not 7,000 TikTok videos of us. It was just an event. It was a moment in time that was, you know, marginally captured. I mean, the records, they're okay in my opinion, but they're not really as good as what we were. I just think it's better left with just kind of a mystique, like: Wait a minute, what the fuck was that? I can't find anything online about it. That's actually an asset.

I really miss Vance. I've worked with a lot of artists and famous people, and…it's funny. Vance got an opportunity to audition [to play bass] with Billy Idol. He didn't go. And then later on in life, I recorded Billy Idol, and…Vance definitely had that quality of someone like Billy Idol. And I just feel that it's a shame that he wasn't able to really have it happen, you know?

Bruce: Opportunity is when you get the chance to get screwed over by somebody. That’s how it was for us and it still is that way today. 9353 was a functional, serious art-invented machine, but nothing will ever go right with 9353, it never will. We’ve never been paid for anything. We got nothing. It’s different when you are trying to make a real thing that doesn’t have any signposts from the world telling you what to do or how to be.

Definitely one of my favorite DC area bands.

They were a tiny bit before my time, however. I did actually buy the second album when it came out in 1985.

....and they were gone before I even got a single chance to see them live in the 80s.

However they did reunite for a small set of shows in 1993, and I saw them live in Richmond, VA at the Floodzone (without Dan though, he had split before that)

Count Gore De Val featured a 9353 music video on late night Channel 20 as well.

Good times. <3

"Opportunity is when you get the chance to get screwed over by somebody." - Brilliant! That's about the most punk rock sentiment ever.