Un-Jewed

On my father’s final trip to Budapest, he showed me the very place he thought he'd left Jewishness behind forever. He hadn't, and as I grapple with Gaza, I wish things were different.

I remember it like it was yesterday, though it was half a lifetime ago.

October of ’96; Budapest cinematic under unrelenting rains. Seated beside my father in the back of a hired car, the mood was thick and difficult to parse. We were here on a grim farewell tour to say goodbye to friends and family. It was only a few months since he’d revealed the diagnosis. Now he had six months left to live.

My father directed the driver to a nondescript alleyway somewhere in Central Pest, then asked him to stop before the arched entryway to a walled courtyard. My father and I got out. In his rain-streaked trench coat, he looked frailer and more drawn than usual. We looked through the entryway in silence.

Across the weathered cobblestones of the courtyard was an ancient building with whitewashed walls. It was a scene seemingly out of time; come nightfall, I could easily imagine the walls lit by guttering torchlight. My father quietly cleared his throat. “This,” he said, “is where I came to register for the Labor Service.”

That was in 1944. The Labor Service—Munkaszolgálat in Hungarian—was Hungary’s homegrown Holocaust. Marketed as a program to employ those unfit for military service, its true aim was to separate Jews, communists, and other enemies of the state from their communities. Sent to perform backbreaking slave labor, they were used for jobs like clearing forests, or as grunt workers during the Hungarian Army’s doomed march to Stalingrad. Roughly fifty thousand laborers accompanied the troops; perhaps seven thousand returned.

What my father didn’t say—but what I understood perfectly well—was that this was the place he stopped being Jewish.

When I was growing up, my father would barely admit to our Jewishness.

It’s only now that I see how persistent a subtext it was. Once, when I was no older than eight, I asked him about it. “One can be Hungarian or Jewish,” he told me. “Not both.”

The problem was that Jewishness was everywhere. Our family home was filled with books, many on the story of the Jews and their trials: The Holocaust, the Middle East wars, the never-ending cycle of trauma, exodus, and rebirth. But with no one to explain our family’s place in them, I was left to draw my own conclusions. Over time, I came to understand Jewishness as a more or less continual state of unbelonging. And so, like my father, I more or less elected to walk away from it, to pretend it wasn’t true and anyway, it didn’t matter.

Of course, the problem was that everything—my cultural references, my bookishness, my anxiousness—gave it away. Even my surname—Hungarian, not Jewish—was most certainly chosen by my ancestors to disguise their true origins.

And of course there’s my face. Once, during my punk days, my band played in Toronto with a sassy all-girl group called Chicken Milk. “Are you Jewish?” asked the guitarist. When I cautiously answered in the affirmative, she gave a knowing nod. “Thought you were a Heeb!” she crowed.

In retrospect, I was probably just being flirted with. Still, there was no getting around it. As a result, I’m too Jewish for non-Jews and not enough for the actual ones. I don’t celebrate any Jewish holidays, never attend synagogue, and cringe at the sound of klezmer music. I feel a quiet pit of shame that I don’t know the meaning of even the simplest Hebrew words—I recently had to look up shabbat (that’s “sabbath,” in case you’re unaware).

And then there’s Gaza.

Hours after the Hamas assault of October 7th, 2023 began, the day was already being memorialized as “Israel’s Pearl Harbor.”

But in sharp contrast with the America of early 1942, the days when Israel is celebrated for its pluck and its resilience are long gone.

Believe me, I get it. I have no desire whatsoever to defend Israel’s military response, which seems to me shockingly punitive and needlessly lethal to innocents. And yet it’s impossible to ignore the streaks of rank antisemitism in the pro-Gaza demonstrations: Israeli soldiers are “Zionist butchers,” their political leadership “bloodthirsty fiends.” Is the issue that Israel’s is behaving brutally, that it’s allied with America, or that it’s Jewish? I honestly can’t tell.

I spoke recently with a close friend; her son attends a college that’s hosted especially heated and violent pro-Gaza demonstrations. She doesn’t support Israel’s response either, but she can’t comprehend her son’s indifference. “I don’t understand why he doesn’t engage with it,” said my friend. “Why won’t he stand up against the rank antisemitism?”

“Imagine how it must feel to identify as a Jew in that situation,” I said. “I get why he’d want to keep his head down.”

“No, that’s not it. I just need to explain more about the Holocaust to him. Then he’ll see.”

Will he? During my one visit to Israel, in 2006—which happened to coincide with a different war against Hamas and Hezbollah—my sense was that the Holocaust was as alive and healthy as ever.

Here’s the thing: unattended trauma does not heal; it festers. Israel’s present campaign stinks of unprocessed grief. The oppressed have traded places with the oppressor, but no one’s the better for it.

As a Jew, I feel like I’m supposed to support Israel’s actions. But I don’t, any more than I support the massacre that Hamas perpetrated on October 7th. On the rare occasions I can bring myself to even engage with the news feed, I lose track of present time. What flashes through my mind instead are the antisemitic caricatures and broadsheets my father saw all around him when he was a boy. Confronted with incontrovertible proof of how the rest of the world saw him, he did the only reasonable thing: He simply decided he would stop being Jewish.

Which brings me back to that alleyway in Budapest, all those years ago.

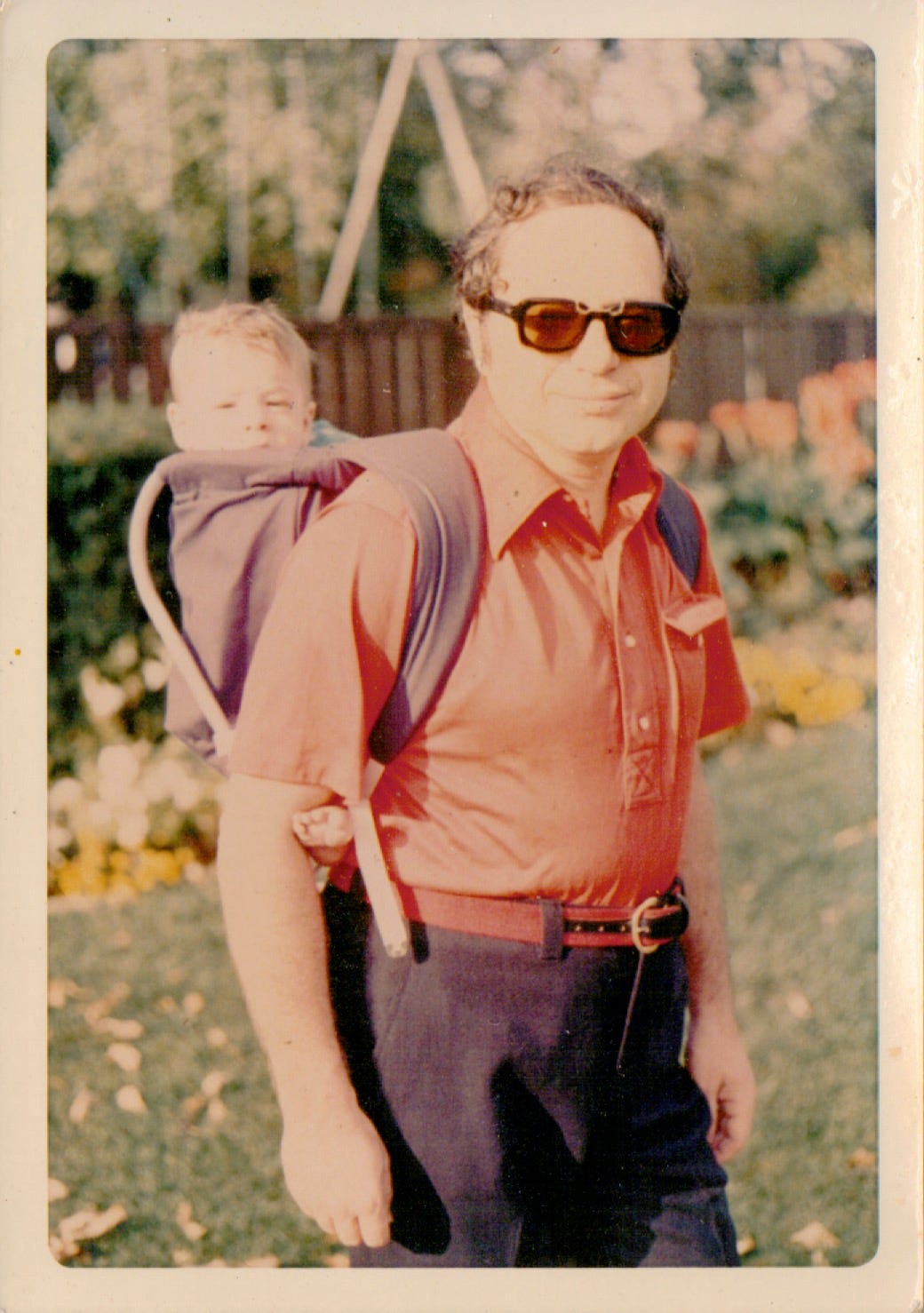

As my father and I stood in silence, I remembered the story he’d told me years ago. That when he was called up for the Labor Service in 1944, he came here—all of sixteen years old—and stood in a long line of young men just like him, all waiting to see what would happen next.

My father grasped desperately for a sign. He looked up to where the line snaked through a doorway in the building’s flank. With no fanfare or parting of the clouds, he recognized that what awaited him inside was death. That if he walked through that doorway and signed his name on the ledger, his life would be over.

Without a word, my father turned and stepped out of the line.

A startled murmur arose behind him, but he didn’t turn around. No one stopped him; no one followed. He walked out through the archway—the very same one we stood before, fifty years in the future, and he kept going. To somewhere, anywhere but to what awaited him here. He kept walking, faster and faster, his gait steady beneath a jackhammering heart.

There was one other thing. Looking at the line of boys standing in the hot sun, my father told me he saw only sheep. This moment was his point of separation from the Jews who had become just bleating livestock. But if this was where he chose to cut that umbilical cord, he did a lousy job of it. It would continue to trail after him, a red and angry appendage that would never completely heal.

Without another word, my father and I turned and got back in the car.

It’s half my lifetime since my father has been gone, but I’m still untangling his legacy. I wish he’d left me with a different relationship to our Jewishness, but I suppose that was his karma. Caught between selling out Israel, my father, or myself, all I’m left with is my own, troubled inheritance.

“Imagine how it must feel to identify as a Jew in that situation,” I said. “I get why he’d want to keep his head down.”

This is really sad, to be honest. Weird how this is basically the feeling your Father had when he stepped out of the line. He didn't want to show that side of him. I know Israel's response in Gaza has been brutal, but I don't think people who have nothing to do with Israel's response should be feeling like they need to keep their head down.

I am nominally Jewish, appalled in equal measure by Gaza, Hamas’s precipitating butchery and mounting, flagrant anti-semitism. Yours is one of the few essays on these intertwined horrors that I could bear to read. Thank you.